14.4 Frontend-Backend Infrastructure ⭐

This section includes a mandatory Assignment ⭐

You've probably heard the terms frontend and backend, but maybe you are uncertain as to what they mean. In this checkpoint, you will learn about the difference between frontend, backend, and infrastructure. These will tie back to the previous checkpoint; in combination with APIs, these architectural elements allow for a user-friendly interface, an effective processing engine, and a reliable structure for exchanging all the data necessary.

By the end of this checkpoint, you should be able to do the following:

- Explain the difference between frontend, backend, and infrastructure

- Describe how those are tied together with APIs

FE, BE, and Infra

Modern computer systems are run by a combination of servers and applications. Industry professionals refer to this combination as a stack. When discussing a stack, you'll refer to broad functional areas. These areas are called frontend (FE), backend (BE), and infrastructure (infra).

A product's frontend technology is what users can see and manipulate. But what, exactly, falls into this category? Frontend technology includes web applications, mobile applications, television menu systems, and any other interface where users can enter inputs, manipulate information, and make decisions.

Backend technology, on the other hand, consists of the many services and tools that allow the content to be presented to the user. The backend includes file storage, databases, processing capabilities, and other systems provided by the application, other applications, or the operating systems that underlie the features provided in the frontend. It also includes services that are hosted remotely, in the cloud, via APIs.

Infrastructure refers to the computers, network connections, hard drives, and other hardware that run the frontend and backend software. The infrastructure may also do other work, like managing database services, running operating systems, configuring servers, and managing file storage systems.

But what do these areas really look like? Well, imagine you're a PM at Dropbox, and you're working on file management in the iOS mobile app that allows users to browse, upload, and download files. Dropbox stores those files in the cloud and tracks other important data, such as account information, how a user's folders are organized, and who has access to a user's shared files. In this example—what are the frontend, backend, and infrastructure elements?

In this case, the frontend is the iOS mobile app. The product's backend is made up of the services that download and upload files, read folder structure, and set file permissions. The infrastructure is all the servers running the backend programs like storage. The infrastructure also ensures that there is enough storage space for future uploads, creates backups to protect user files, and stores all the data necessary for the programs to work.

Just like players on a sports team—such as a pitcher or shortstop in baseball—your developers specialize in roles specific to frontend, backend, or infrastructure technology. However, there are also full stack engineers who are skilled enough to work on all parts of a product. As teams grow and products become more complex, individuals and teams will typically specialize in one area of the stack.

The video below provides more information about tech stacks.

It's essential for a product manager to understand—and know how to discuss—the technology relevant to each area of the stack. This knowledge will help you make informed product decisions and establish a constructive working relationship with your engineering teams.

Frontend

The frontend is the easiest to understand. It is what users interact with most often—on a website, desktop application, or mobile application. Some applications, like Dropbox, have multiple frontends: a mobile app, website, and desktop app. But each frontend uses the same backend and infrastructure accessed via APIs. Each accesses the same file information, regardless of whether a user is using the iOS app on their iPhone or the Windows 10 app on their PC.

Multiple frontends

These days, most applications have multiple frontends: an iOS app, an Android app, a Windows app, and so on. Typically, these frontends are characterized by the operating system they are built for; applications require specific programming to work with each OS because device manufacturers do not support interoperability. For instance, the Windows application for Dropbox won't run on macOS, and vice versa. By providing different frontends, Dropbox allows users to conveniently use the product across several operating systems.

Each frontend is often written in a different programming language. Windows applications are often written in the C## programming language, iOS in Swift, and Android in Java. Developers typically specialize in one programming language or operating system. A company or department may have multiple teams working on a product to support multiple frontends, and each team may focus on a different area of the stack or operating system.

Developers can write a single frontend for an application and try using it across operating systems. However, the same code will look and feel very different on different operating systems, and features and functions may be supported in different ways. For example, menu functionality and options can vary widely across operating systems. A product must also consider physical differences; operating systems can be tailored to a specific range of devices and their hardware, such as screen sizes and input methods (keyboard or touchscreen, for example).

A team may also customize a product's frontend to better fit with the aesthetic and functionality of an operating system. For example, the buttons and navigation on Apple products are different from those used for Windows or Android. Matching the look and feel of an OS makes an application more intuitive and user-friendly. Users often feel more comfortable using a new product if the interface and navigation feel familiar; they don't have to learn how to use it.

As a product manager, you'll want to consider the operating systems used by your target audience. What percent of users use which operating systems? This information will likely influence the priority of each frontend and the composition of your development team. Also, supporting multiple frontends adds overhead costs. Whenever you need to make changes that affect the user interface, your team will have to fix each frontend individually.

Push versus pull

But the frontend doesn't operate in a vacuum. Changes affecting the backend of a product can prompt updates—updates that the frontend should reflect. For example, consider a shared file on Dropbox. A user has shared a photo file with a friend, and the friend uploads a photo that replaces the shared photo. The original file owner should be alerted when this happens, right? There are two ways for the system to notify the frontend—and the user—of the change: with a push approach and a pull approach.

In the push approach, the system's backend recognizes the new file in the Dropbox account and pushes information to the frontend app. This is also how a phone receives SMS messages: the phone provider's server pushes the message to the phone, then the phone notifies you about the new message. Pushes are useful when changes happen frequently and the user expects to be notified right away.

In the pull approach, the frontend periodically asks the backend if there have been any changes. This is typically how social media apps update a user's feed: the app frontend checks for new items at regular intervals, maybe every few seconds or minutes. The updates seem fairly immediate to the user. But that new story or post that suddenly appears in the frontend might be a minute or two old, depending on when the frontend last requested an update. In these cases, the frontend has a cycle: it asks the backend about updates, sets a timer, and then asks the backend again when the timer is up. Lather, rinse, repeat.

The pull strategy is a good one to use when users don't need instantaneous response time. However, it's still in a development team's best interest to create a product that provides timely updates. It's also a useful approach for products used on unreliable connections, such as mobile apps. The frontend can pause updates while it's disconnected, then it can request a new update as soon as it's reconnected.

Static versus dynamic

Some application frontends change frequently, like how headlines automatically update on news sites. Other interfaces, or aspects of an interface, rarely change, such as the news sites' logos. Items that can change in a frontend are called dynamic, and items that don't change are called static.

Most modern applications are highly dynamic. Many are also interactive, which means they have a level of dynamic content that is actively changing in response to information put in by the user or about the user. For example, after a certain time of night, a user's phone screen may adjust its brightness. Similarly, if a Facebook user interacts with a specific friend often, Facebook will eventually prioritize that friend in the user's feed.

To better understand, consider your Dropbox app. A user's list of files is dynamic, and the list can change as items are added or deleted. If you add a file to your Dropbox via your desktop frontend, the list of files on your Dropbox mobile app should update dynamically in response. But the menus, buttons, and icons are probably static, or they update rarely. As users interact with the app, the frontend and backend communicate to display folder contents or files. This dynamic content is visible in the app as updates are made.

Identifying what's static and what's dynamic in a product's interface helps frontend developers work with backend developers to create APIs that power your product. And, as product manager, you'll work with both groups to pick a push or pull approach for your product, ensuring that the right data gets exchanged at the right time.

Backend

The backend includes all the services needed to make the frontend experience possible. It's the worker behind the scenes, the one storing, processing, and sending almost all the data so that the product's frontend looks and behaves as the user expects it to. Consider your Dropbox app again. Once a user opens the app, the static content will appear immediately. As the user engages with the product, things change: new folders are added, files are renamed, documents are deleted. As this happens, the frontend and backend start continuously exchanging data dynamically.

Programs and services—often using APIs—require input from each area of the stack, like information about user preferences from a database, files from storage, or processing for searches. Backend developers write applications that process the data that the frontend depends on, like storing files, pushing updates, accessing account details, and more. Those backend programs run on the application's infrastructure and access data from a variety of sources, like hard drives and databases.

Databases

Dropbox needs to store a lot of data. It stores info about each user and their account—it knows each user's name, email address, and password. It stores all the files and folders added to every account. And when users revise those files, Dropbox logs and stores each revision. That sounds like a lot of work. What, exactly, is tracking all of this information?

Data like this is stored in a database. A database is kind of like a gigantic spreadsheet—one in which cells in the sheet link to cells in other sheets. Following this analogy, Dropbox might have one spreadsheet with a row for each user, and there might be another sheet with information about every file that has been uploaded. The row for each file identifies the user who owns each file; to connect this information, the file sheet links back to the users listed in the user sheet. There may also be a spreadsheet of users who don't own a file but can still view or edit one. Their level of access must also be recorded. And all the files in a user's Dropbox account are also stored on a file server that is similar to the hard drive on a computer. The database must keep track of these file server locations so the application can retrieve the files when necessary.

The amount of data an application needs to store—users, files, and much more—can be enormous. In fact, it can be many times larger than any spreadsheet could store. You'll explore databases in more detail in the next module. For now, it's important to know that they are specialized storage systems built to keep, read, and write massive amounts of data with incredibly high performance. These allow a level of abstraction; the APIs can exchange data with different frontends without the frontend programs being directly linked to the database.

Synchronous and asynchronous

Some APIs are designed to work very fast. For example, when a user taps a folder in a Dropbox account, they immediately see an updated list of files in the folder. To do this, Dropbox made an API call to retrieve that folder's content. A process like this is called a synchronous process because it happens in real time—you click the folder, and the new data arrives immediately. Synchronous APIs are used in interactive applications to optimize user experience.

Other APIs and processing can take more time. For instance, downloading a log of every change that has ever occurred in a user's Dropbox account would take a while. Collecting and processing all that data takes time! Instead of completing this task in a synchronous way, the Dropbox server processes the request and emails the user a link to the log. This is known as asynchronous or batch programming. It is used when processing requests will take a long time, or an unknown amount of time.

Backend design choices affect user experience. If a feature or function requires a lot of processing power—and may take some time to complete—be sure to design an experience that sets users' expectations correctly by indicating how long it will take. Understand how data is processed in your product so you can collaborate with engineers and designers for an effective interface.

Infrastructure

In some fundamental ways, technology infrastructure is a lot like highway infrastructure. The hardware and services that keep an application running can be compared to the bridges, tunnels, and freeways that allow cars and trucks to get from one place to another.

Running web servers, databases, file servers, and other systems is a complicated process that requires specialized skills. Your infrastructure is overseen by a team, and that team is usually called infrastructure, operations, or dev ops. And as a product manager, you must understand how infrastructure supports and enables your product. Below are terms you should be familiar with when discussing the infrastructure impact of product decisions.

CDNs

Think about something as simple as a home page. Even a basic home page is made up of many smaller files, including CSS, JavaScript, and images that download separately. When a web page is loading, it is downloading these assets. This can take time. So as you design a product, you want to consider ways to speed up the process.

Content delivery networks (CDNs) are specialized web servers for delivering static content files as quickly as possible. They also handle geographic routing, which attempts to connect users to the nearest data servers. These services expedite the downloading process, reduce operating costs, and are relatively inexpensive.

However, CDNs can also cause infrastructure problems. For instance, Dropbox may update an image on their home page, but some users may still see the old image. Some infrastructure changes take time to spread across all your servers, so make sure you discuss any potential issues in using CDNs and other distributed storage systems with your infrastructure team to make the best possible decision.

Cloud computing and containers

Computers need hardware for storage, CPUs, RAM, and more. These can be expensive. The technology is continuously evolving and improving. Keeping up and maintaining the hardware is a huge endeavor. Also, a company's needs fluctuate—you might have 10 users hitting your APIs at midnight and 10,000 hitting them at noon. It's a waste to offer computing power for 9,990 users who aren't there. And if 10,000 users suddenly surge to 100,000, you need a way to quickly scale up your infrastructure.

Cloud computing has become the dominant method of addressing this infrastructure need. Instead of building out their own hardware infrastructure, companies will essentially rent computing power from another company. This allows a company to access more (or less) CPU power, web servers, storage, or databases as needed. Cloud computing will likely be part of your product's infrastructure. You don't need to understand the details in-depth, but you should understand its role and how it's used to facilitate discussions with your team.

The most widely used cloud-computing provider is Amazon, under the brand Amazon Web Services (AWS). AWS includes many other services, like Redshift and RDS for databases, CloudFront and S3 for content storage and delivery, and EC2 for virtual servers. Other popular cloud-computing providers include Google Cloud Services and Microsoft Azure.

Putting it together

Imagine the process required to load the list of files in a Dropbox folder to an iOS app. There are several actions and procedures happening on the frontend and backend:

- A user touches the folder they want to view in their iOS Dropbox app.

- The frontend of the app generates and sends an API request to Dropbox API servers requesting the folder file information.

- The request is sent over HTTPS with the user's verified account information.

- The Dropbox web server receives that request.

- The web server passes that request to the backend application that handles these requests.

- The backend app sends a query to the database requesting the list of files for that folder.

- The database sends the list of folders to the backend.

- The backend generates an HTTPS response with the list of files and passes the response to the web server.

- The web server sends that back over the internet to the iOS app.

- The iOS app processes the response and renders that information to the user's screen.

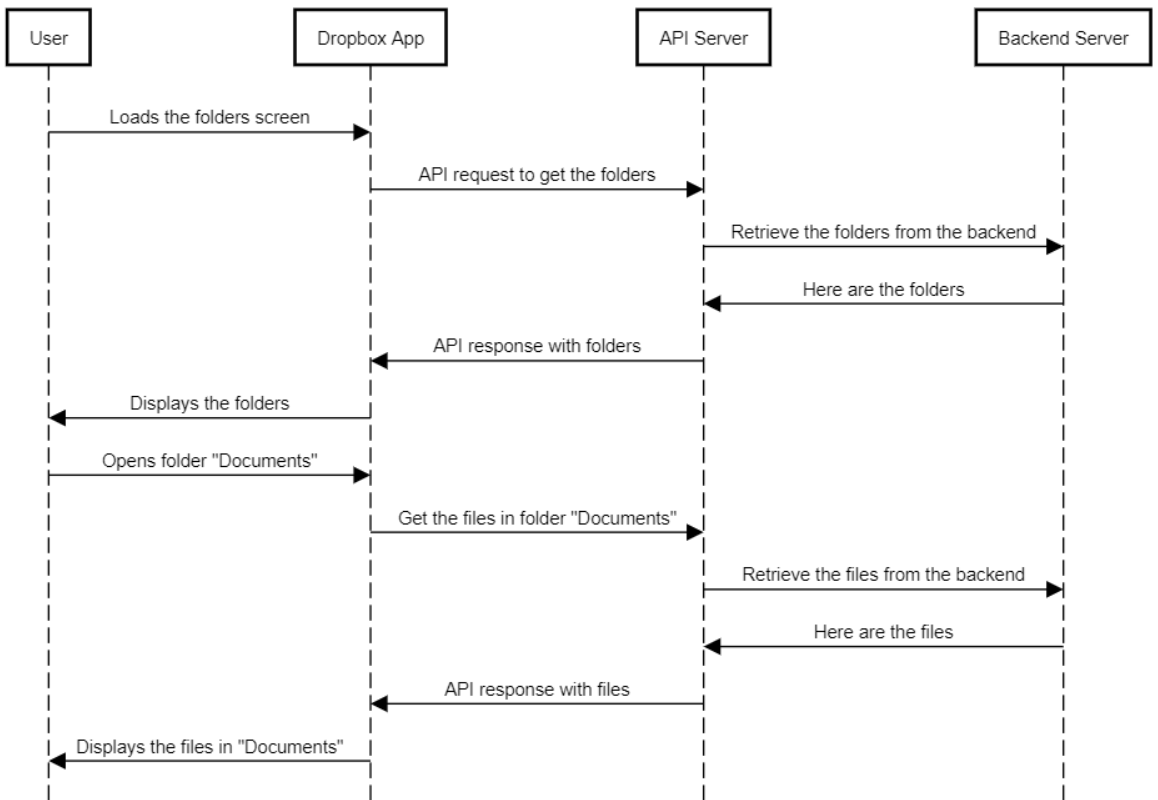

It's pretty complex! And that's how nearly every internet-powered application works—sending API calls, processing data on the backend, and sending back information to the frontend. And these processes and relationships provide internet users worldwide a rich and seamless application experience. Interactions like this are sometimes shown in sequence diagrams that show all the actors in the system and how they interact over time. You read it by going from top to bottom, following the arrows as data is exchanged between the systems.

Diagrams like the one above are called sequence diagrams, and they show how various systems work together over time. For instance, this sequence diagram serves as a graphic representation of the steps outlined above.

A sequence diagram is read top to bottom; the top is where the event starts. Each lane is one of the systems that makes data exchange and processing possible, and the horizontal lines show how data is passed and processed. A sequence diagram is particularly useful if there is a complex series of actions that involve many systems—an illustration of the events can be easier to understand than a text description. You'll likely develop or review a sequence diagram with your development team.

Assignment 10 ⭐

Go to the Product Hunt home page and take a screenshot of it. Annotate the parts of the page indicating which are static and which are dynamic.

For each dynamic component, list the data that it needs to access in order to display its information (this is the data that would be in an API to feed that component). Submit a copy of your annotated screenshot beloin the respective slack channel.

Submission

Submit your links in the slack channel #assignment-10