4.2 Lean Customer Development

If product-market fit is your goal, then you need a few tools to help you get there. Many companies use techniques like the ones you'll learn about here to help them get to product-market fit faster. Many of these methods have been popularized by startups, but now even larger companies are seeing the value of the startup mentality, or lean product development.

In short, this means every company is trying to do more with less. As leaders who are responsible for creating new products and features, product managers have a specific responsibility to lead this process, navigate the obstacles along the way, and eventually find the best outcome for their product, users, and companies.

Now you can dig into the lean methodology and see how it can help you make better products faster.

By the end of this checkpoint, you should be able to do the following:

- Describe how customer development and the lean methodology drive product success

- Create hypotheses that you can prove for creating better products

A quick intro to lean

The concept of lean as it relates to products was first introduced by Eric Ries in his book, The Lean Startup. It's a fabulous read for any aspiring entrepreneur or product manager.

Lean startups and lean product development are ways companies can gain confidence in their products before they allocate large amounts of resources to develop them. Building new hardware and software products is incredibly expensive and time-consuming. This is especially important for startups who are often losing money every day while they develop their products. The lean process helps companies avoid overspending on products and ideas doomed to fail.

There are many competing methodologies and processes for getting there. This checkpoint is going to focus on customer development and the lean startup process. These are good foundations for building your own methods of learning from customers.

Customer development

Customer development is a specific method for creating new products and business ventures. It was created by Stanford professor Steve Blank. It's a set of techniques to help you understand a market, identify opportunities, then scale and grow your customers and company to capture that market.

The customer development process

Customer discovery is the process of understanding your users, their problems, their purchasing behavior, and any other issues that can help you identify their needs for a product solution. You're done when you've identified your target customer, your product's value proposition, and solutions to those customers' problems.

Customer validation is the process of creating your sales process and your business model. In this phase, you're working on a scalable, repeatable method to create predictable sales. If you're not able to do this, then you need to go back a step and try to discover new insights that will create healthy sales growth.

Customer creation is the process of expanding your customer base—finding new customers for your current product and new ways to sell to existing customers. In this phase, you're monitoring the market and competition closely while ensuring your business grows profitably and efficiently.

Company building is the transition from a company focused on learning and adapting to an executing company that has reached peak maturity and is running on all cylinders.

For the sake of this lesson, you're going to focus on the customer discovery process.

Customer discovery

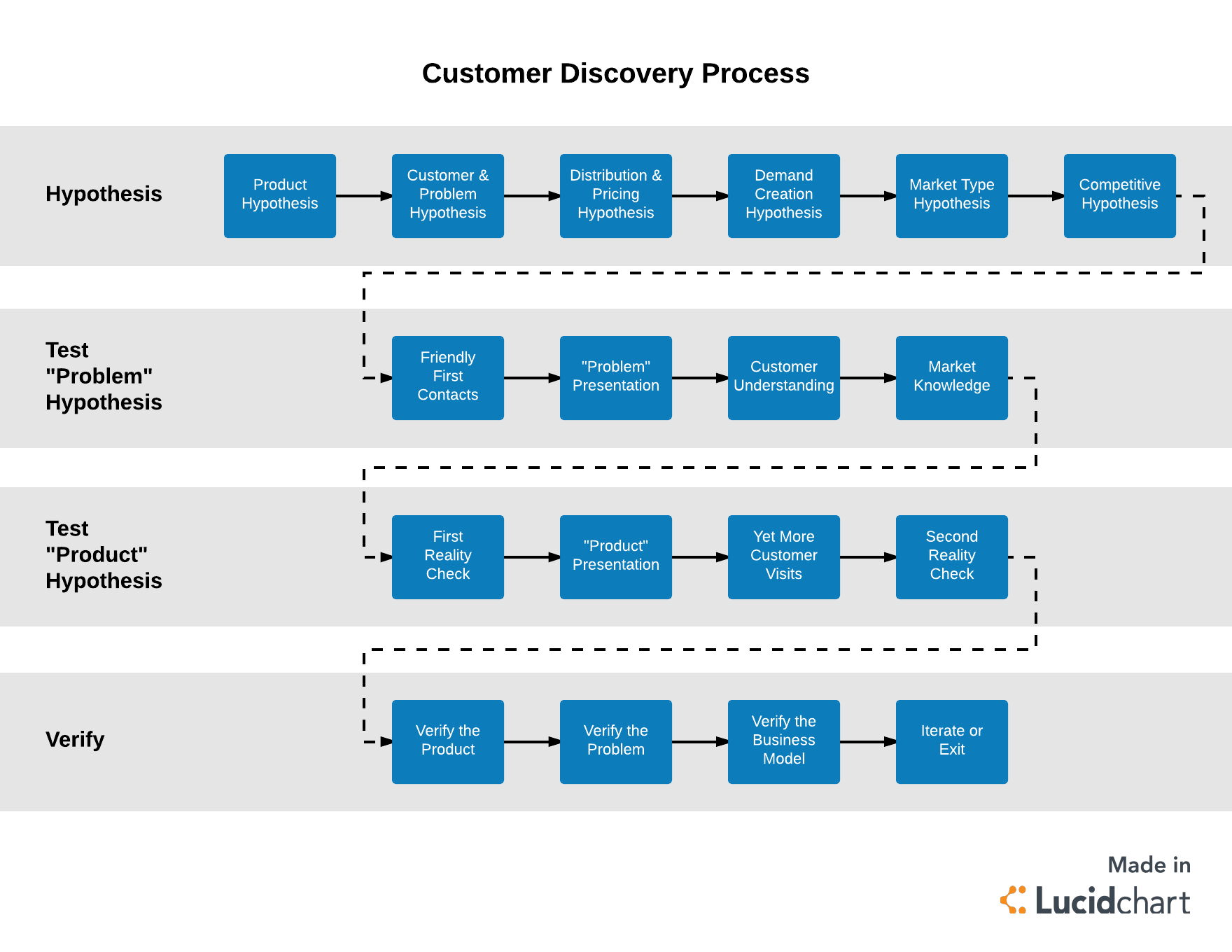

Customer discovery is about understanding your users and their needs. The main parts of the discovery process are creating your hypothesis, testing the problem, testing a product solution, and verifying your solution. It's a cycle:

For example, say you work at Twitter and are working on ways to reduce harassment online. First, you write out your hypothesis.

We believe that requiring users to use their real names on Twitter will reduce incidents of harassment and abuse. We'll know we were successful when monthly reports of abusive content show a decrease of 25% compared to today.

Then, present your understanding of the problem to people in the market—customers, experts, media, and others—to see if you've identified the correct problem.

You talk to experts in the field, Twitter users who have been harassed, and your coworkers. They generally think that anonymity is a primary reason why there's so much abuse online.

So you start to pitch your solution to them. You haven't built anything yet; you're just discussing what's possible to see if it would really address the issue.

What if everyone had to give their real names? Experts and victims of harassment seem to think it would go a long way towards fixing the problem. Your coworkers worry that it would have a huge, negative impact on the company's goals of retention and growth.

And then you evaluate what you learned.

While it seems like using real names could solve the immediate problem of harassment, the downsides are too severe for the company to push this forward.

So you go back to the drawing board and write a new hypothesis. This cycle continues until you've found the right balance of problem and solution.

The lean startup cycle

The lean startup is a set of principles and methods for helping startups get to product-market fit. There's a lot in common between this and the first phases of customer development, especially the concept of testing hypotheses. And even though it has startup in the title, companies of all sizes use these methods to create new products and services.

The key to the lean startup is this cycle of building your product: build → measure → learn.

Take a moment to follow this to understand how the process works. There are three actions—build, measure, learn—and three results that you create from those actions—ideas, code, and data.

- You learn about your customers, their problems, and how well current solutions work for them, including your own product

- The results of your learning are ideas for taking the problem you learned about and developing solutions for them

- You build the ideas you came up with

- Your code is the artifact of your building

- You launch the code and measure the results

- Your measurements create data that you can analyze

- You learn from your data, and the cycle repeats

The goal is for this process to take days to weeks to complete—working smarter rather than harder.

Lean modern product development

As mentioned earlier, the reason why these methods are popular in product management is that you want to make decisions with high confidence and strong evidence while using fewer resources and less time.

Looking at product management from the outside, you might think that product managers add any features they want to their products. This solution-based thinking is the opposite of the way you should approach it. It's time-consuming and expensive to build a feature and wait for results. And if you're wrong, you've wasted time and resources when you could have learned the same lesson with less.

When you think lean, you're framing your work as hypotheses and experiments. This has several advantages over just building it. First, it makes it clear that this is the best guess, not a definite solution. People outside the product team often think the team provides specific solutions. When you frame your work as solutions, others expect your solutions to always work. When you frame your work as experiments, you lower the expectations of your outcomes, and it creates space for you to explain why it did or didn't work.

Second, you can prove that a hypothesis did or didn't work by looking at specific metrics moved or outcomes achieved. It's much harder to look at a solution and see if it solved a problem. Other people will decide if this feature solved their problems on their own terms. When you write your own hypothesis, you get to choose the success criteria and can declare victory (or failure) on your own terms.

When you have a hypothesis, you have

- A problem that needs to be solved

- A group who will benefit from that problem being solved

- A potential solution to the problem

- Evidence that we (and not others) will use to tell if we succeeded or not

Then you can run an experiment around that hypothesis to see if it's true or not. If it's true, that's great. If not, then try again.

The video below provides insight into how to turn an idea into a hyphothesis and how to turn that hypothesis into concept notes.

Thinking in hypotheses

A hypothesis is a proposed explanation for something that you observe. You might remember these from science class. A hypothesis contains assumptions based on evidence. You can take a hypothesis and run an experiment to see if it's valid or not. Tech companies are obsessed with data and evidence, so applying scientific methods to product development is a natural fit.

This is also a key skill in finding product-market fit. There are many features or products which could solve a problem for a group of people. Some solutions are better than others. Using hypotheses helps you focus on what makes this solution better than any other one.

For example, say you're interested in the problem of finding babysitters for children. You've personally experienced the trouble yourself, you think others have the same problem, and you think there's a novel approach you can create to solve this.

You could summarize your thoughts in a single statement, like this example:

I believe that creating a trusted marketplace for finding babysitters for busy parents will result in happy parents and babysitters. We will know we were successful when we can book 100 babysitters in my town in one week.

Or maybe if you're a product manager at YouTube and you're thinking about ways to increase viewer engagement, you could say this:

We believe that creating a social network around YouTube creators will result in increased views from YouTube viewers. We will know we're successful when social network users increase their weekly views by 10%.

Or even a small improvement to a small feature like this may work:

We believe that adding a Login with Apple button to our application will increase registration from all users. We will know we're successful if our registration conversion rate increases by 5%.

Parts of a good hypothesis

Hopefully, you've noticed that those hypotheses are written pretty consistently. In general, a good hypothesis looks like this:

We believe that [building this feature] for [these users] will achieve [some benefit]. We will know we're successful when [this outcome happens].

Now, dissect the parts of a hypothesis further.

[building this feature] — You need some ideas about what type of solution will address the issue at hand. It doesn't need to be fully formed at this point, but it does need to be specific enough to show a clear path forward.

[for these users] — It's easy to throw features out in the world. It's much harder, and it's your job to understand the users and their relationship to your product. Remember—product is about solving people's problems. Choose your users well.

[some benefit] — This is the value proposition that you're offering. It's what makes the solution unique or interesting. Be careful about just repeating the benefit of the feature. For example, if you automate a repetitive task, the benefit is not that the task is automated; that's the feature. The benefit is that the user has time for other things.

[this outcome happens] — This outcome should be something specific and measurable. Think back to your science experiments. The point of an experiment is that you validate your hypothesis through specific tests. The same applies here.

Writing good hypotheses

Here are a few additional rules that will help you craft better hypotheses.

- Test the riskiest assumption

- Figure out the smallest way to test it

- Observe problems

- Talk to customers

- Get expert advice

- Use "should we" over "can we"

To illustrate each of these, look at these through the lens of that babysitting matching service from before.

Test the riskiest assumption. Imagine you're going to build that babysitting matching service. What's the hardest part? Which part has to succeed in order for the whole thing to succeed? Maybe you need to find ways to build trust between the parent and babysitter. Maybe it's that both parties want to ensure secure payments. Find that risky part and test it first.

Figure out the smallest way to test it. It would be easy to just go and build a whole babysitting matching app with profiles, video chat, payments, and more. But maybe there's a simpler thing you can do to test it without all the other parts. If you only saw a sitter's references, would that be enough to make you trust this sitter?

Observe problems. One way to find good hypotheses is to witness people in the act of solving their problem "the old way." For instance, you could go to a friend's home while they search for their own sitter. You notice they engage entirely through text messaging, which means you might be able to skip video chat and just do text chat for your app. Do the same for the sitters themselves. Watching them do the work is a great way to find opportunities where you can improve the process.

Talk to customers. Sometimes you can't find people in the act of solving these problems, so the next best thing you can do is talk to them about it. You'll learn interview techniques in a later checkpoint. For now, focus your interview on the way they solve the problem today and find the biggest issue within that.

Get expert advice. As discussed before, you can always find people with experience in the field to see if they can give you insights. For example, find people who used to be babysitters and learn from their experience. You could contact people in related fields, like nannies or home cleaners, that likely face similar issues.

Use "should we" over "can we." One place you can get hung up when coming up with solutions is on the question of can we solve the problem in a specific way. The answer is yes, you always can. With infinite time and developers, you could solve any problem. A better question is should we do it this way? What are the pros and cons? And are there better ways of doing it?

What to do when you're told what to build

One issue that will come up frequently during your career will be when someone who outranks you orders you to build a specific feature or product. Maybe your CEO wants you to add a Login with Apple button to your login form, or a key customer demands that you create a custom integration with their content management system.

Many times, these requests will go against your instincts. For example, none of your users use their Apple sign-ins, or the development work for the custom CMS integration would take months of work.

You generally have two ways you can handle this. First, you can just do what they say. You have a strong defense because you "didn't have a choice." It doesn't feel good, but it's good enough.

Second, you could take what they say and turn it into an experiment. For example, you could say, "Instead of building the full Login with Apple button, what if we run an experiment where we put a fake login button on the screen and see if people click it? It will be much simpler, and we'll save weeks of time if it doesn’t work." You'll usually get a yes.

By thinking in hypotheses, you can turn a huge amount of work into a little experiment. The next checkpoint will go into detail about taking hypotheses and building products from them.

Practice

Choose a company of interest. Imagine you are interviewing for a job at the company, and you're asked the common interview questions below. Record yourself answering both questions. Treat this as both job search prep and a way to test your understanding of this topic.

- Do you have experience with lean development?

- How would you implement lean methodology here?

Choose a product for which you can get access to three of its users. These can be friends, coworkers, or—bonus points!—strangers you observe or watch in a public space (like people using an electronic catalog at a library or an automated order system at a movie theater). Make a list of problems users encounter. Determine which of the problems is most common and/or severe. Think of a potential solution to one problem and write a hypothesis for it.