4.3 MVP 🎯

This section includes an Activity 🎯

MVPs are all the rage in product management. You'll hear the question "What's the MVP?" over and over again at work and in your job interviews. This checkpoint will focus on this essential tool in a product manager's toolkit. You will learn what MVPs are, how to ship them, and how to answer those interview questions about them.

Developing technology products is expensive and time-consuming. But what if companies could test a tech product without writing code? With limited time and resources, minimum viable products (MVPs) allow companies, and PMs, to verify a product's or feature's chances of success before investing in it heavily. An MVP is a small way to test a hypothesis. It may not look great or have all the bells and whistles, but it does one thing, and it does that one thing well. Or at least well enough to learn if you're on the right track.

By the end of this checkpoint, you'll be able to do the following:

- Explain how MVPs are used to validate ideas for your products

- Propose MVPs based on product hypotheses

What is an MVP?

An MVP can be thought of as a kind of experiment used to test a hypothesis or an assumption about a specific problem. Developing tech is expensive and time-consuming. What if you could test a tech product without writing any code? Or what if you could test it by creating a small part of the product with tech and then creating the rest by hand?

An MVP has these key characteristics:

- It contains the smallest number of features (minimum).

- It delivers the solution to a problem (viable).

- It works today, and isn't something hypothetical (product).

Why use MVPs?

The benefits of MVPs are straightforward. First, being able to test your hypotheses without relying on expensive, time-consuming tech is invaluable. Your developers and designers will thank you for not asking them to devote their time to building features you're uncertain about.

Second, you need reliable ways to test your hypotheses. If you were 100% certain that every feature or product would be a success, you wouldn't need MVPs. When you only have your best guess, you need methods to prove which hypotheses are right and which are wrong.

Finally, MVPs provide PMs with evidence for making more informed decisions about the design and development of products. They allow you to have a more influential voice in the development of products that you may find problematic. For example, imagine you want to test a babysitting app in a "real" way. You're concerned that your app won't contain enough information to allow parents to choose a babysitter that fits their needs. You write a hypothesis to address this problem.

I believe providing parents with detailed information about a babysitter's profile builds trust in the babysitters I've recruited for my app. We will know we're successful when 10 parents contact a babysitter for an evening.

Developing without an MVP

Imagine what developing an app from scratch—without creating an MVP—looks like. You decide that the best way to do this is to build an app that matches parents with babysitters. You come up with a list of 20 sets of data and then spend a few weeks with designers and developers building the app's features for babysitters and parents. Once it's finished, you get people to test it.

During testing, you run into numerous complications. The app doesn't work on certain phones, and some babysitters omitted key information from their profiles. But worst of all, parents had no way to contact their babysitter of choice. As you investigate the problems, you learn that parents only used about 20% of the included data to select a babysitter. You also discover that there were datasets that parents wanted but that weren't included.

As you can see from this example, spending weeks or sometimes months developing an app that doesn't work well is neither minimal nor viable. Could you have learned about some of those problems without building the entire app? Yes, if you had built an MVP instead.

Developing with an MVP

Now imagine that, before building the app, you ask some babysitters to volunteer to fill out a simple paper form with four or five pieces of key information about themselves, such as their experience and availability. You then ask parents for their feedback on the information you've collected and learn that there is additional information they would like to know about each babysitter. Once you have gathered that additional information, the parents express their satisfaction with the data.

With this method, you were able to validate your hypothesis without having to build the app. With this validation, you can now start building the app with confidence, and all it required was a piece of paper and a few minutes' time from volunteers. This is the essence of an MVP. You can test your hypothesis rapidly in low- or no-tech ways.

Creating great MVPs

There are several principles to keep in mind when creating an MVP. Before reading about each of these principles below, first watch this video by Y Combinator that previews what it takes to create an effective MVP.

Focus on a customer

Making something for a small group is better than making something for everyone. For example, Facebook was originally created for college students and expanded to new groups over time. Friendster and Myspace were similar products but were created at the outset for everybody. Interestingly, Facebook became successful, while Friendster and Myspace shrank to serve only niche audiences.

Spotify is another example of a successful product originally created for a relatively small group of people (Sweden) before expanding worldwide. The benefit of catering to a smaller audience is that it limits the risk that comes with trying to please everyone and trying to solve too many problems at once.

Focus on one problem

When you develop an MVP, first choose your customer, and then choose a single problem of theirs to solve. This means learning which problem is the most important to solve.

Imagine you want to capitalize on people's misgivings about Facebook and decide to target teens with your own social networking service. Facebook solves a lot of problems—how to share photos, how to create videos, how to send people money, and many more.

Which single problem could you solve to convince your target audience to use your service instead of Facebook's? You could focus on a problem that Facebook already solves, but do it better. Or you could find a new problem to solve.

Test the riskiest assumption

If you face several problems and you aren't sure which one to address first, choose the riskiest one. There are usually one or two problems that are more difficult to build, that have high uncertainty, or that could make or break your product. Choose those over the easy hypotheses.

For example, imagine you have a new technology that can record every moment of a user's day, and you have an early version that's ready for testing. There are many potential risks here. The technology could be unreliable, or users could start using it but give up. Or maybe users could choose not to sign up because of privacy risks. Which of these do you believe poses the biggest risk to your product's success? Make that determination, and then address that assumption.

Why test the riskier option? Because an MVP allows you to fail safely. If you proceed to build your product without testing the riskier assumptions, you may eventually discover your product is failing because that risk came true. On the other hand, if you come up with a viable solution to a risky problem at the MVP stage, you'll effectively remove one of the biggest barriers to your product's success.

Measure it

It's not enough to just run a test. You need to be able to measure your MVP's results. For example, imagine you work for Twitter and want to launch a feature that automatically blocks offensive content without any user intervention. What could you measure to know if the feature is successful? You could measure people's total engagement time, the number of complaints you receive, or the number of posts and responses that people make.

It's not enough to just measure an outcome. You also need to know which metrics to measure. If you launch a Twitter blocking feature and you measure the page load speed, are you measuring the right thing? Choose your metrics well.

Compare it

When you test your MVP, a good practice is to compare your MVP's metrics to the same metrics in the absence of the MVP. Even better, you can compare the two at the same time. You can run a test with two groups of users, providing one group with your MVP while the other group doesn't get it. When you compare the metrics of the two groups, you can be reasonably assured that any differences are due to your MVP and not other factors.

If you're unsure which tests to run, you can compare several variations at once to determine which is best. For example, Google once tested 40 different shades of blue for links to see which would increase clicks the most. You can perform similar comparisons with colors, text, images, and more.

Is it minimal enough?

The hardest part about creating an MVP is trying to find the most minimal version to test. For example, go back to the babysitting app. You could test your hypothesis by building the app and getting people to use it, but that's not very minimal. On the other hand, using paper and matching by hand may be too minimal, as users might not react to it the same way they react to a digital experience.

If you're struggling to determine if your MVP is minimal enough, ask yourself these questions.

- What resources will I need? This helps you determine if it's possible to run. If you need a 12-person team, it's probably not minimal enough. If it's just you and a piece of paper, you may want to consider getting closer to the real experience.

- How will I measure the outcome? How do those measures compare to the real version? This helps determine if you have measurable metrics and goals. If not, you may be wasting your time on an MVP that proves nothing.

- How much work is required to turn this MVP into the real version? Measuring the amount of effort (in hours or days) is a good way to discover if you have the bandwidth to take this on.

- How will users react to this MVP compared to the real version? This will help ensure that the MVP is close enough to the real thing that the reaction will be similar.

MVP models and examples

Choosing the right MVP model can make or break your experiment, so think carefully about your choice before you begin. Several common approaches are described below.

Product mockups

One way to test your hypotheses is to create a mockup of the actual feature. A mockup is just an illustration of the actual feature (you'll learn more about mockups in a future module). Mockups can range from a picture that looks exactly like the final version of the product to a drawing on a piece of paper.

A great example of a successful mockup is Twitter. Twitter began its life as a series of drawings on a pad of paper. Imagine a time when Twitter didn't exist, and you were trying to explain it to someone. Showing them a drawing and explaining the details with a story is a great way to describe what the product will eventually look like and how it will operate.

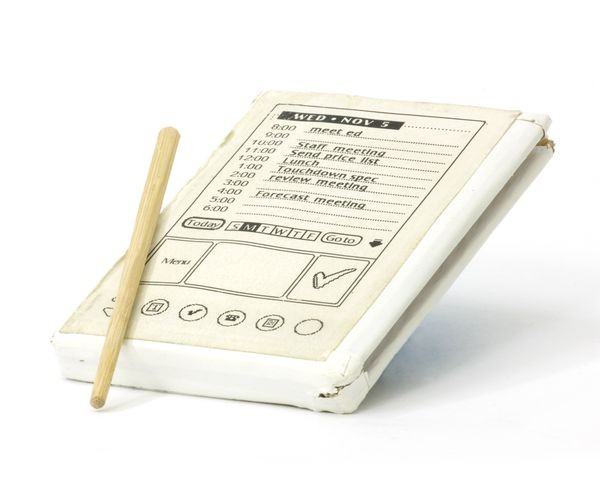

Similarly, the PalmPilot (a precursor to smartphones) was first a model made out of wood and paper. When the designer wanted to look something up, he pulled out this block and used it as if it was the real thing.

Demo videos

Dropbox started as a demo video. Before there was a product, Dropbox's creators shared the video below on Digg. The video convinced thousands of people to sign up for what soon after became Dropbox beta.

Landing pages

A landing page is a sign-up or information page that guides users to take an action expressing their interest in a product. Many companies use landing pages to advertise their software. Potential users search for a product on Google, select the first result, and are then taken to a page where they must complete a form to access a demo.

Landing page tests are good for testing different pricing schemes. You can randomly display for some people a subscription for $10/month and others $12/month, then compare the conversion rates of the two groups. You can also feature different capabilities of your product to see which sets generate the most sign-ups. This is called an A/B test (you'll dig into much more detail about these later in this course).

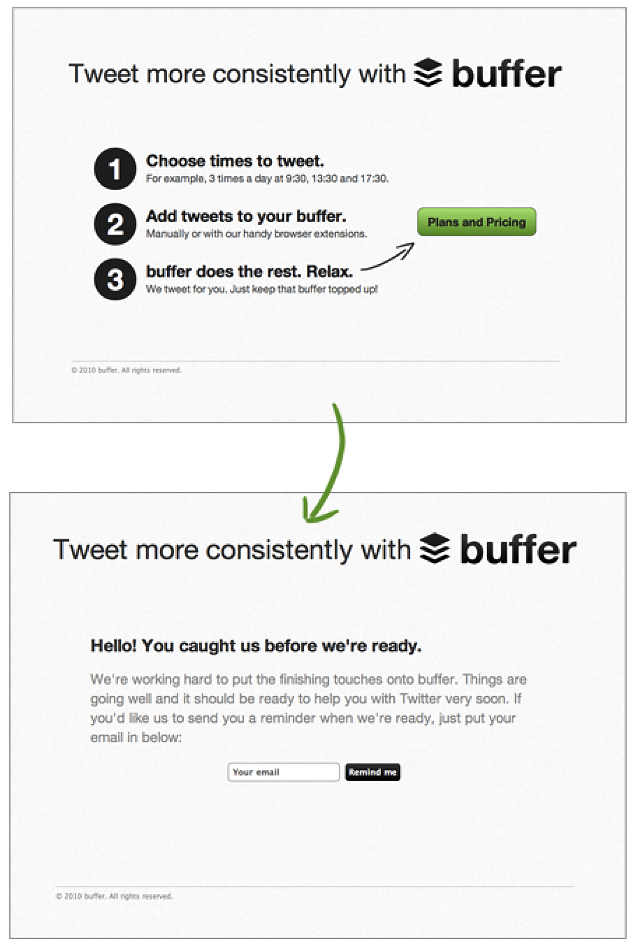

Buffer, a product for managing social media postings, started as a landing page. It advertised and drove visitors to a website that offered a service that didn't yet exist. Users could sign up for a notification when it was ready, which is how Buffer acquired their first users.

Crowdfunding

Crowdfunding sites like Kickstarter and Indiegogo are great places to see MVPs in progress. Many projects posted on those sites are not quite done. Their creators are looking for funding to help finish the process. Getting enough people to fund your project is a sign that there's product-market fit for the thing you're making.

One famous crowdfunding success-and-failure story is Pebble. Pebble was a smartwatch that was the most successful Kickstarter to date, raising nearly $10 million in 2012. However, their business folded in 2016 due to a combination of poor sales of their future products, a shifting market for wearables, and several failed acquisition talks. This illustrates how a successful MVP does not guarantee a successful product.

Wizard of Oz

A Wizard of Oz MVP is one where you have a product that looks like the real thing on the surface but is powered by people behind the scenes.

A great example of this is Zappos.com. Zappos began by having people take photos of shoes in stores and then posting them online. Zappos workers would then buy and deliver those shoes when someone bought them from the Zappos website. It's important to note that you can fill in the gaps in your technology by using people to complete your MVP.

Other MVP types

Below are a few less common types of MVPs.

- Software prototype. This is a small subset of the full product created as a demo or a functioning prototype. This is one of the most effective ways to show off a large technology advancement, although it requires more resources and is less minimal.

- Build it for one. This is a version of your product built for just one customer. The risk here is that the customer's needs might not overlap with other customers' needs, but it could accelerate finding the product-market fit or uncovering issues you'll need to address.

- Concierge. This creates an experience delivered entirely by a person that is replaced by technology bit by bit as you learn more about what is needed. This is a great way to learn from your customers, but it is also time-consuming. The difference between concierge and Wizard of Oz types is that your users know that the concierge service is delivered by people, while the Wizard of Oz type tries to hide the people behind the digital experience.

MVP shortcomings

As valuable as MVPs are, it's important to recognize that they are not a panacea. You need to be aware of a few challenges that PMs commonly encounter when creating them.

First, not everyone is familiar with the concept of an MVP. Some believe it describes the full feature rather than an experiment or a partial feature. Some stakeholders or customers may be disappointed when presented with the results of an experiment rather than a complete solution.

Second, an MVP is only as good as the hypothesis it tests. If you choose to test only the easy parts of your assumptions, you could be misled to believe that your product is set up for success. Think back to the babysitting app. What do you think the hard part of that app was to test—the design, building trust, getting people to sign up, or something else altogether? What features would you choose to test?

Finally, you could create an MVP that proves your hypothesis, yet still end up with a full feature that doesn't work. For example, you could run an MVP for your babysitting app and receive positive feedback, but when you launch it to everyone, it could fail to gain any traction. Your experiment can succeed, and then your product can fail.

Expanding the MVP

There's an ongoing debate in the product community about how far you need to go with an MVP. Does it need to work? Should it be sellable? Should people have emotional reactions to it? You'll hear different variations on the theme of MVP. Here are a few of them.

Minimimum lovable product (MLP) and minimum desirable product (MDP)

MLP and MDP are essentially the same. The goal is to elicit an emotional reaction to your product, and that may take more than just an MVP. That usually means adding a few of those extra bells and whistles as well as polishing the look and feel more than you would with an MVP.

Minimum buyable product (MBP) and minimum sellable product (MSP)

The MBP or MSP is a usable version of the product that you can sell. For example, think of all the beta or early release products you've heard of. Many times, companies don't charge for using those versions of products. Once out of beta, however, they start charging for it. This is the gap between an MVP—not quite good enough to sell—and an MSP—it's ready to sell.

Minimum functional product (MFP)

An MFP is a version of the product that "works." An MVP may take some shortcuts or require lots of manual work. The MFP fills in the gaps and offers a complete solution, even if it still requires some design polish or is lacking a few features that would make it more effective.

Activity 🎯

Read through the three outcomes described below. Write at least two hypotheses and describe an MVP to help achieve each outcome.

Note: You will create two hypotheses and one MVP for each item below.

- Gmail wants to increase adoption of shared email lists for non-business individuals (for example, a mailing list for the family, softball teams, church members, etc.).

- On-demand beer delivery mobile app

- An app that recommends local events to you based on things you like