13.1 Agile Development

By now, you've probably heard the term agile (sometimes Agile) multiple times—in the product blogs, in news sites and online communities you are following, at networking events, and even in some previous checkpoints. You know that being agile means being able to move quickly and easily. But you may be wondering—what exactly is agile development?

Agile is an umbrella term used to describe different types of iterative development. As you've probably realized, it is currently a very popular software development methodology. Like other software development methodologies, it is a set of practices designed to enable cross-functional teams to work in an organized, structured way. While many organizations describe themselves as agile, there are many flavors to being agile, and approaches will vary.

In this checkpoint, you'll learn about the core principles of agile development and explore how agile differs from other development methodologies. As a product manager, you'll help organize the development workflow and make sure that your team is completing a variety of tasks. In this work, agile will be one of the key tools in your toolbox.

By the end of this checkpoint, you should be able to do the following:

- Explain the difference between agile and waterfall development

- Explain key agile terms, such as Scrum and Kanban

Software development methodology

Software development methodologies are processes for planning, building, testing, and releasing software functionality. Companies and individuals prefer different methodologies, and some people are very passionate about the methodology they believe is best. As you gain experience in product management, you'll likely develop your own preferences.

Software development methodologies typically include the following elements:

- Approaches to or templates for documenting product requirements

- Practices for managing team collaboration

- Methods for tracking progress

- Techniques for proactively identifying and resolving issues that are likely to cause confusion or delays

Regardless of their variations, all methodologies seek to establish a standard way of capturing and communicating how the product should function. By establishing a standard process, the team can focus on building a product rather than spend time and energy figuring out the best way to share status updates or discuss concerns with the team.

As with most things, trends in software development change; new versions of established methodologies emerge constantly. Many new iterations offer improvements that have become best practices. But again, no matter the methodology, the aim remains the same. Each establishes a process that a cross-functional team can use to resolve issues effectively and focus on producing a product that meets their company's objectives.

From waterfall to agile

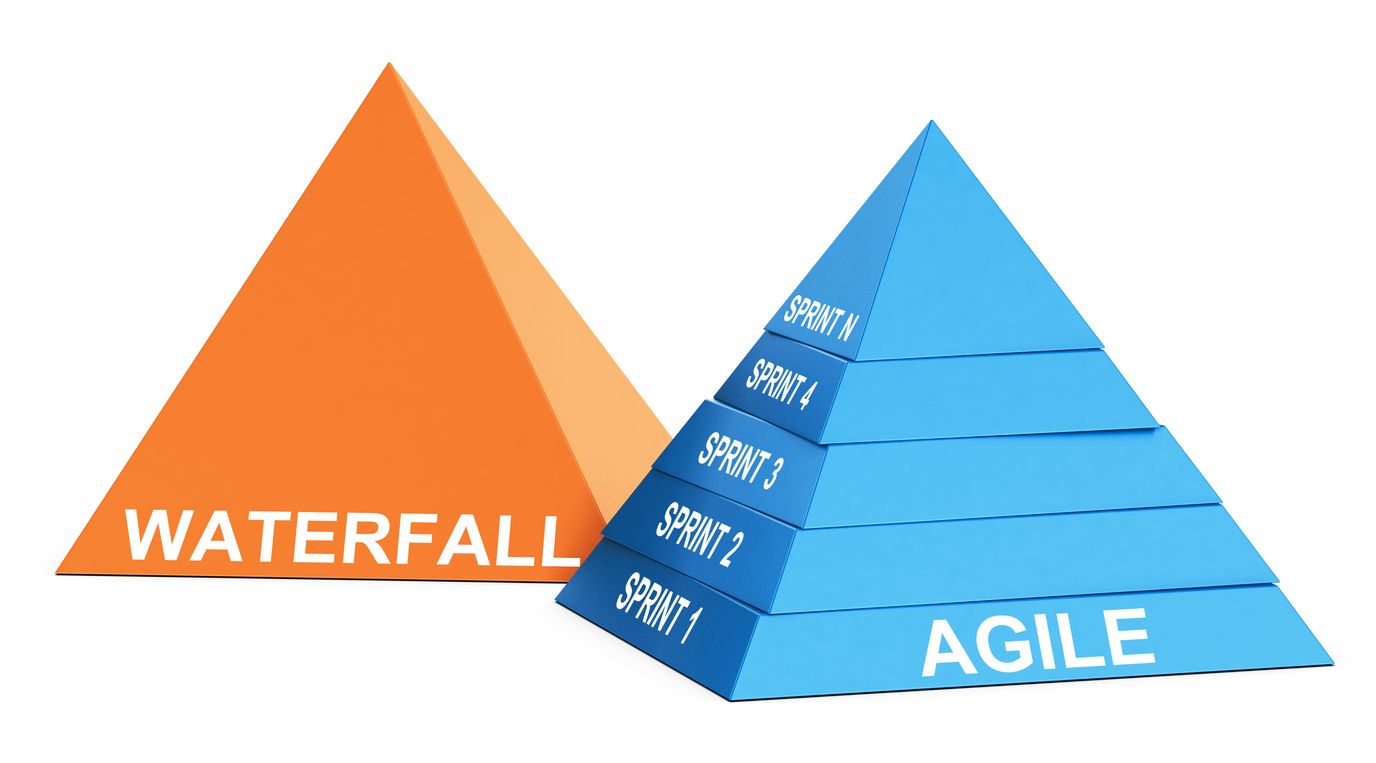

Waterfall development is the traditional model for software development methodologies. Although the model is now considered fairly outdated, you'll need to understand how it has informed approaches to development.

As the name suggests, the waterfall model refers to a cascade of water moving downstream with specific drop-offs. The model organizes development in the same way. Software is built step-by-step in a one-direction process—like a waterfall. This model ties into older visions of the product development process. Initially, product managers and analysts determined that the process consisted of defining requirements, then designing from the requirements, and then implementing the design.

They then created long, complex documents covering all the requirements necessary for creating a new product. They believed that establishing the entire scope of the project would make planning more effective. But as development got underway, teams needed to make changes and updates, which had significant ripple effects. Keeping documents and teams up-to-date was messy and confusing. As a result, projects were typically over budget and behind schedule.

In 2001, a group of thought leaders in software development presented an alternative. They published the Agile Manifesto, which was a response to the pain points of the waterfall method. They felt that waterfall was too focused on planning and documentation and didn't facilitate collaboration between business and engineering professionals. When using this method, many teams suffered from poor communication and a lack of iterative progress. This led to projects that didn't deliver on the original objectives or align with customer needs.

The Agile Manifesto sought to change all that by focusing on some new principles:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

In agile, business and engineering teams work iteratively and on an ongoing basis to develop products that are both customer-centric and practical in their technical design. Large public releases may be months apart, but smaller internal releases occur more frequently so the team can see how changes affect other parts of the product. Business stakeholders have a tangible product to test in field research, and issues in these early iterations, like an unexpected bug or flawed feature design, can be immediately addressed.

Agile quickly became a popular approach and spawned several methods inspired by its core principles. It is now the foundation for most contemporary software development. That said, you will still encounter elements of waterfall, especially in larger organizations or on very complex, inter-related technology projects. For some projects—such as developing software that monitors air traffic at an airport—lots of advanced planning and testing makes more sense than iterative, incremental progress. Many organizations and teams also customize agile methodologies to meet their needs. You may work with a hybrid of practices and approaches.

Agile methodologies that you're likely to encounter include Lean Startup, Extreme Programming (XP), Kanban, and Scrum. Each of these is worth exploring further, but this checkpoint focuses on two of the most popular agile methodologies: Scrum and Kanban.

Scrum

Scrum is an agile framework that helps teams organize their work. It's popular in software development but is slowly starting to be adapted for other fields involving complex knowledge work, such as research and advanced technologies.

The terms Scrum and agile are often used interchangeably, but there are distinctions between the two, which are highlighted in the video below by Darcy DeClute.

Who's involved?

There are several roles involved in running a Scrum process. Note that these are roles, not titles; they can—and often are—performed by the same person. Keep reading to learn about the major players in a Scrum environment.

Product owner

In some companies, the product manager also acts as the product owner. In others, the product owner is a separate role. How are the two roles different? A product manager thinks about strategy, creates roadmaps for time horizons typically varying from three months to three years, and maintains communications with clients and internal business partners. Their most important function is working with stakeholders to prioritize what is being developed.

Product owners (PO), on the other hand, distill that knowledge into clear, actionable tasks for the development team. A product owner acts as the bridge between different groups; they communicate business needs and priorities to the development team. Engagement and active collaboration with the engineering team make up the majority of a product owner's time, and they are much more focused on the near future. They think in weeks, not months or years.

Scrum master

The Scrum master (SM) facilitates all of the sprint meetings and takes the lead on resolving obstacles the development encounters during the sprint. In a way, the SM role is like a project manager role that requires additional skills. The SM works with the product owner to ensure backlog items are well understood and actionable so the development team can make progress on them. The SM coaches the development team on Scrum principles and practices and promotes self-organization and early identification of issues. The SM also works across teams, and with other SMs, to make sure product development stays on track.

Development team

In Scrum, each development team typically consists of three to nine people. The size is important; the goal is for each team to be self-organizing and able to execute on each sprint's tasks without a lot of complex coordination. Every member of a development team is a technical specialist and is focused on building and deploying the product. But depending on the product, the team may include diverse experts. In addition to engineering and QA professionals, the team could include architects, statisticians, and data analysts, for instance.

What's involved?

Time to learn some Scrum lingo! From epics to stand-ups and sprints, knowing these terms will help you talk the talk when you interact with product professionals. So get your notebook ready, and take note of the terms, rituals, and structures that make up Scrum.

Epics and stories

Scrum is all about breaking work into more manageable tasks. And typically, those tasks are part of a larger enhancement. Even a minor adjustment to a user flow can involve several implementation tasks, and any new data field the user inputs must have a database location to be recorded. Furthermore, there must be plans for where and how that data is used elsewhere in the product. This is where epics and stories come in.

A user story is a tool used in agile to capture a software feature from the perspective of the end user. The story includes who the user is (such as "as a very hungry person"), what they want ("I want to know which delivery options will be quickest") and why ("so I can choose the right option"). Stories like this help create a simplified description of a requirement or feature. An epic is simply a large and complex user story. In the next checkpoint, you'll take a deep dive into epics and stories and even begin to develop your own.

Sprints

Sprints are the cornerstone of iterative development. They are specific blocks of time—sometimes called timeboxes—in which the team focuses on completing specific tasks from the backlog. Typically, a sprint lasts two weeks, but some organizations use one-week or one-month sprints. Development projects or product releases are accomplished through a series of sprints. By establishing short blocks of time and an intentionally narrow scope of work, the team is able to focus on specific, predefined tasks and avoid getting pulled in numerous directions. Using sprints, teams can be more efficient, reduce task complexity, improve communication, and increase productivity.

Daily stand-up

A daily stand-up meeting (sometimes called a daily scrum) is a brief team check-in. It's called a stand-up because it was conceived as a short meeting where people stand up; the inconvenience of standing up for long periods of time is meant to remind participants to keep it brief. Some teams actually do this meeting standing up huddled around someone's computer. And some teams use a traditional conference room. Either way, it should last no longer than 15 minutes.

The goal of this meeting is to give the development team time to report on progress and issues. Each member of the development team comes prepared to discuss the work they completed yesterday toward the sprint goal, what they plan to complete today, and any obstacles or risks to meeting the sprint goal.

Any issues identified in the daily meeting are addressed in a separate breakout session with only the relevant team members. The Scrum master (usually that's you—the product manager) tracks obstacles or risks and figures out how to resolve them, taking into account that any distraction of a development team member will cause delay in accomplishing sprint tasks. The status of issues that need resolving will be reported in subsequent daily stand-ups.

Product backlog

The product backlog is the ordered list of product requirements that is defined and maintained by the product owner. This list can include new features, nonfunctional requirements (such as architecture upgrades for increased stability), or bugs fixes.

Anything identified as a prioritized improvement will be in the product backlog, which functions much like a to-do list. The backlog items may have user stories, data mapping, workflows, or interface designs attached to them in order to provide the needed details to the development team. As the team considers items for a sprint, they will discuss any additional user specifications and estimate the time that each item will require to complete. Some items may require more effort than expected. The team will identify a practical strategy for breaking tasks into smaller, more manageable portions that they can develop in iterations.

Product backlogs can be long and a bit overwhelming. It's difficult to imagine if you haven't worked with them before. If your current place of employment is using agile, try asking a friend on the product or engineering team to show you the backlog. It's essentially just a long list, but it's useful to see for yourself.

Sprint planning

At the beginning, or kickoff, of each sprint, the whole team determines what will be accomplished. They work from the backlog, but there will be discussion about where to begin. For instance, the team may pick a priority item and a few related but nonurgent items for a sprint because it would be more efficient to do the programming and infrastructure work for all of these items together. However, if there are significant client or market pressures, the team may pick unrelated but urgent tasks for the sprint.

Sprint planning meetings usually last several hours, depending on the length of the sprint. The first half of the meeting is spent identifying the work that will be done. During the second half, the technical team digs into the work. They ask questions, map out their approach, and confirm their time estimate for what can be accomplished in the upcoming sprint.

Demo

At the end of each sprint, the development team demonstrates the work completed. This is usually a quick clickthrough reviewing the new functionality, but it can be a more significant presentation if the team is demoing a whole release or completed feature.

This functional demonstration serves as a check-in for everyone. The demo gives development team members a better sense of the updates they didn't work on, and the product owner can confirm that the work completed in the sprint meets customer needs. The demo may reveal new issues or prompt adjustments, too. Based on the demo, the team may modify the items in the backlog or reprioritize tasks to be considered in the next sprint planning meeting.

Retrospective

In an effort to improve efficiency and collaboration, the team should end each sprint with a retrospective meeting, or retro. In this meeting, the Scrum master leads the team to reflect on the sprint. The meeting should be a safe space in which team members can openly answer several questions:

- What went well?

- What did not go well?

- How could we improve productivity for future sprints?

The team takes actionable learning from this discussion and applies it to future sprints. The goal is to foster continuous improvement.

Kanban

Kanban is another popular agile framework. It places a high value on helping everyone on the team see and understand the workflow. It provides context and clarity about the work that the team's completing, and it draws attention to bottlenecks or delays.

Kanban relies on several visual elements. The Kanban board has three work groupings—not yet started, in progress, and completed—which are usually presented as columns. Each column has cards in it, and each card represents a task. The cards are very similar to user stories in Scrum. In a real-world office setting, the cards are usually standard-size Post-it notes. Using Post-its is practical for the board and forces the team to write each task succinctly to fit on a Post-it. There are also Kanban options in many project management software tools, some of which you will learn about in greater depth later.

Organizations will use different titles for the columns. When mingling with Scrum, the work not yet started is the backlog. In other cases, it may be labeled "Requested" or simply "To do." The column for work underway is often customized or subdivided. When using Scrum, it will represent the current sprint's tasks. A common subdivision is to distinguish if a task is being developed or is in testing. An additional column or identifier may be used to flag cards facing an impediment to progress, often referred to as blocked. Some teams may only use the main three columns for their current sprint with additional columns for the overall backlog and cards from completed sprints.

Like all agile methodologies, Kanban emphasizes communication and flexibility. While Scrum uses specific roles and the sprint approach to timebox and streamline work, Kanban limits what is considered in progress to reduce distraction. When a team has too many items in progress, it's probably facing a bottleneck. An excess of in-progress tasks often represents an inefficiency, prompting the team to identify strategies for pushing forward on certain tasks and moving other tasks back into the backlog.

Agile in practice

Agile methodologies were a reaction to what was not working in the elaborate planning of top-down organizational structures. Before agile, executives who were tackling a large project—like developing a new software—wanted to reduce their risk, so they focused on planning and managing work to get the desired results. These same worries still exist. Larger, more traditional organizations know about agile development, and many have worked diligently over the last two decades to apply its principles to their work. But of course, top-down expectations sneak in.

Even if your team is perfectly applying all the principles of agile, you might work for an organization that still uses waterfall practices. Often there are good reasons for this. For instance, maybe you work for a financial institution that has zero risk tolerance for presenting client information incorrectly. Your team has developed beautiful enhancements for the company technology platform, but that platform uses customer data that is used by 22 other teams. In a case like this, the team responsible for that customer data will likely require extensive testing before any products touching their data can be released.

Agile practices can be applied at an institutional level, too. Some organizations apply a Scrum of Scrums, for instance, to scale the practices to the complex environment of a large organization. This approach follows the same Scrum model of daily stand-ups and sprints, but the participants are Scrum masters who are updating one another to properly coordinate their projects. A Scrum master may use the Scrum of Scrums meeting to identify a solution to a problem a developer raised. For example, imagine your developer can't access a necessary internal API because it is being upgraded. In this case, the SM overseeing the upgrade can coordinate with your SM to provide access to the API version in development. Or they may confirm that the upgrade changes won't affect the API calls your developer is using, so designing in the old version is just fine.

Company culture also plays a role in the successful application of agile methodologies. Agile is flexible, and organizations can tailor practices to their needs. But sometimes flexibility can undermine effectiveness. Executives who don't fully understand agile principles may encourage the organization to be more agile when really their only priority is to make development faster. Some organizations won't focus enough on improving estimates or communication. For instance, a team may be working in sprints, but they won't complete their tasks if they haven't calculated accurate time estimates. Or a team member may waste time fixing an issue that someone else has already resolved if the issue isn't discussed in the daily stand-up. Doing agile right takes work and a true commitment to the principles.

Finally, company leadership and business models will also influence how priorities are established. For instance, imagine that you've used rigorous customer research to identify several key features that are clear winners for upcoming product releases. However, an executive may insist that another feature is the real market opportunity. Or, your largest B2B client has threatened to switch to your competitor if the feature they demand is not included in the next release. These are very real situations. Ideally, you'll work in a company with less dramatic politics, but as a product manager, you'll need to navigate these challenges. You'll be required to balance objectives and predict stakeholder needs while also fostering a strong and collaborative dynamic with your team.

Balancing it all

The product manager and product owner roles within agile require an ability to balance. Product managers work within—and between—development teams and business partners. Stakeholders will eagerly ask for release dates and specifics on upcoming enhancements. They'll ask about work that's underway and items that are pretty far down the priority list. As a product manager, you'll need to tactfully respond to these inquiries while redirecting your colleagues' focus to the work that supports the product strategy.

Having well-defined KPIs and OKRs are crucial here. They are not only useful for making sure the team and stakeholders understand the direction the product is headed, but they are also valuable for reorienting you on the objectives and success metrics as you pivot from being deeply immersed in technical implementation details to discussing your five-year vision with your CEO and marketing team. The challenge and variety of working to move your product forward among the whole range of stakeholders are what makes product management fascinating.