7.4 Information Architecture 🎯

This section includes an Activity 🎯

In your word processor, where would you find the copy function in the menu? Where would you go to create a new table or to import an image into a document?

Many tech products have a shared problem—how do you organize all the features in a way that makes sense? E-commerce sites have a specific version of this problem—how do you organize all the stuff that you're selling so that it's easy to browse and find a product? And how should you name these features so that users will quickly recognize their function?

Information architecture is the umbrella term for the method used to address these problems. In this checkpoint, you will learn how to organize content to improve your product's user experience.

By the end of this checkpoint, you should be able to do the following tasks:

- Explain what information architecture is and how it applies to digital products

- Use card sorting to create information architectures

What is information architecture?

Information architecture (IA) is the design of shared information systems, especially in digital products. It's especially concerned with the way information can be organized, labeled, and discovered in effective and sustainable ways.

You probably use information architectures all the time, even without knowing it. For example, imagine you have a bookcase filled with your favorite books. How would you organize them? There are many ways to do it:

- Alphabetically by title

- Alphabetically by author's last name

- By subject matter

- Descending by height

- By colors of the rainbow

- By publication date

- By purchase date

- By the location it was purchased

Now review the scenarios described below. For each, ask yourself, "How would I organize my books to make this task as easy as possible?"

- You're looking for a specific book by author and title.

- You're looking for a recipe book, but you don't remember the specific name.

- You just bought a new book and need to add it to your bookcase.

While for the first scenario, an alphabetical sort would be most useful, the second scenario would benefit from a bookcase organized by subject matter. The last scenario, by contrast, would most benefit from a system organized by purchase date.

There's no single solution that solves all of these problems. One way of organizing your books makes some tasks easier but others harder. You have to make trade-offs and choose the organizational systems that will serve your book-finding needs most of the time.

This is an example of the problem that information architecture tries to solve. Now imagine you're starting a new e-commerce site for selling clothing. How would you organize the products you sell? What would you do to make it easier for shoppers to find the right item? How would this affect your process when you add a new item for sale?

IA in products

You see IAs in digital products everywhere, but you may not be aware of them. Review the examples below to dig deeper into IA in different types of digital products.

E-commerce

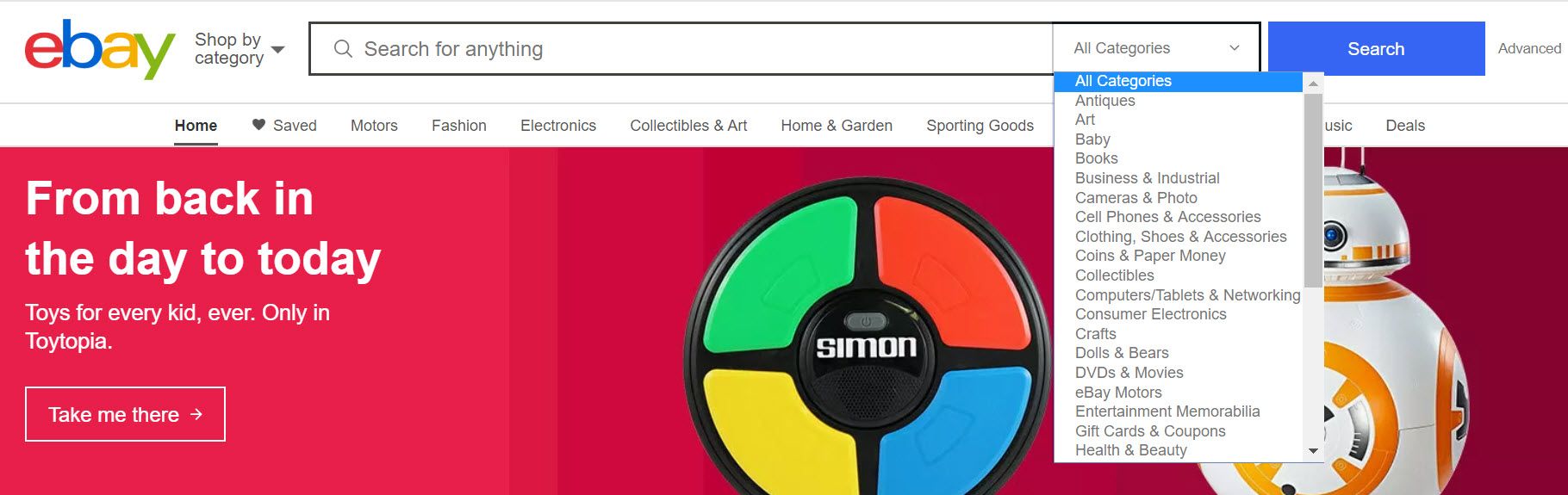

Every e-commerce site has made decisions about how to organize their content. For example, if you list an item to sell on eBay, you have to choose which category it belongs in. The list of categories on eBay is so large that it has several levels of hierarchy, for instance, electronics → cameras → camera accessories → hand grips.

Not everyone will browse those hierarchies to find their items, but the hierarchy system is still important because it powers other kinds of features, like the search on the site.

Menus and navigation

Applications and websites use conventions to show their features and content in an easily recognizable way. On desktop applications, it's common to hide features under menus that run along the top bar or on toolbars with icons. Many apps hide their menu under a three-dot ፧ icon or under a so-called hamburger ☰ icon. And websites use navigational menus to show the top content and help you get around. Take a look at how Amazon organizes its menus, navigation, and commerce items together.

Documentation

FAQs and other forms of documentation also need to be organized and searchable. If you were trying to find information on shipping rates for sending items through eBay, how would you find that? Help content needs just as much thought as any other information. This is especially important if you're creating products for other developers. Most developers consult this documentation when integrating products together. The better your documentation, the easier it'll be for both users and developers to use your product.

Hashtags

Tags are an alternative way to think about content organization. You'll learn about this more soon, but for now, you should think about hashtags as an organization curated by users rather than an organization curated by the product owners.

Content + users + context = IA

When you think about information architecture, there are three main parts you need to consider: content, users, and context.

Your content is the stuff you're organizing. Whether it's items for sale, blog posts on your website, or just information about your product, you need to think about all the items that are being organized or that could be organized in the future. You may not know this, but eBay started as a site selling Pez dispensers. Today, you can find nearly anything on the site, including electronics, homes, and cars. Over time, eBay has had to evolve and grow their categories substantially.

Users are the people you're designing for. Every person has a different model for how the world works, but your products will generally have only one information model. It's your responsibility to find the right balance that works for as many users as possible. For example, if you're trying to make a button to add an image to a document, should it be labeled "Add image" or "Insert image" or "Import image"? Which would make the most sense to the most people?

The context is the situation in which this information matters. For example, you need a different IA for finding clothes in your closet than you need for finding clothes on Old Navy's website. Similarly, the information you need to solve the problem of where you should lunch is different than the information you need to figure out where you should go to buy cat food. Even though both are about locations, you'll have a different set of considerations about getting lunch than you will about going to a pet store. What information is common between them? And what information is not common?

When considering your information architecture, you need to think about all of these together. Even within a single application, you can have multiple users with multiple contexts. In AdWords, some users only have access to reporting and information while other users have access to all the ad bidding, creation, and administration features. How should you organize those features to ensure everyone can easily use the product?

Ways of organizing information

It may seem overwhelming to think about the myriad of ways that you can organize information. Thankfully, there are only a few main ways that you need to consider.

Location or geography

Often it makes sense to lump parts of your product together by location. For example, Craigslist is organized by metro area. If you're searching for a used kitchen table in New York City, Craigslist allows you to limit your search to specific boroughs and neighborhoods. Similarly, Airbnb would love for you to book an experience and a place to stay all at once. That offer only makes sense if your stay dates overlap with the experience dates and only if they're in the same location.

Alphabetical

This one is straightforward, but it only makes sense in certain contexts. For example, sorting A to Z doesn't make much sense if you're looking for new shoes, but it does make sense if you're looking for a specific person in your list of contacts on your phone. If alphabetical sorting doesn't make sense in a specific context, it's acceptable not to include it.

Time or chronological

Time is another simple sorting method—and one which also has depth. Time could refer to the time something was created, updated, or last viewed. There are many variations on how time can affect a user's choices. You might even need several time options depending on the context.

Category

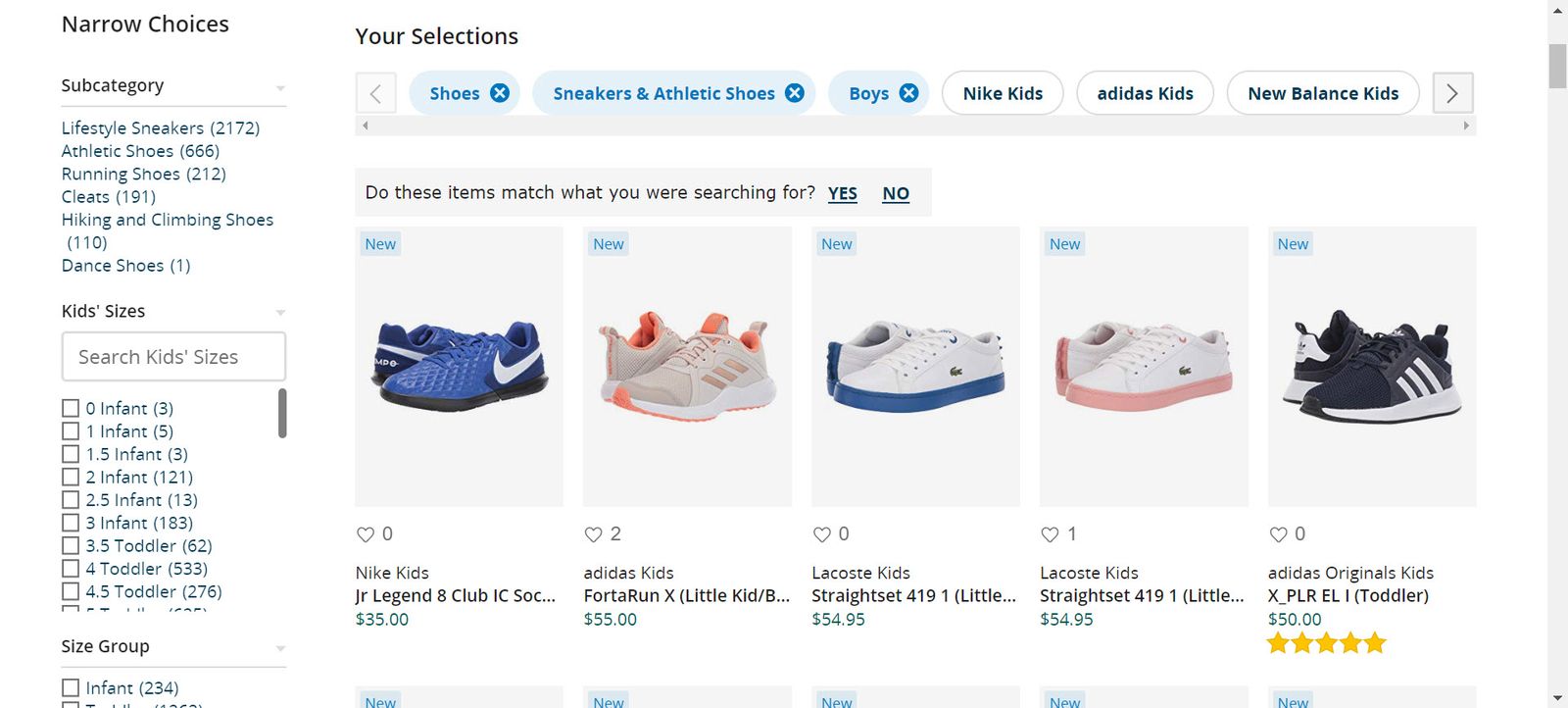

A category is a grouping of similar items using shared characteristics. If you're selling shoes, you could group them by type, color, size, or material. Often it helps to make multiple categories accessible at once for the purpose of searching and filtering results.

Hierarchy

Use hierarchies when your information has a natural structure of precedence or rank. This is often combined with categories, especially when you have large numbers of categories. For example, clothing is often organized in a hierarchy that starts with gender, then moves to the type of clothing (women → blouses). Using categories in combination with hierarchies makes it easier to organize and navigate those categories.

Metadata

Imagine you have a photograph. What are all the possible pieces of information you could store about that photo? The picture is the main item, but there are a lot of other bits of information about it: where it was taken, what's in the photo, who took it, when it was taken, information about the photo settings (ISO, exposure), and more. This information is called metadata—data about the data. In the case of the photo, the main data is the picture itself; all the other information is data about the photo.

Metadata in products most often appears as filters when you search. Think back to the Zappos search filters for shoes. In the image below, the filters for "Boys" and "Sneakers & Athletic Shoes" are on. For the filter options to be useful, each product needs to have this information filled in completely. Every product has different metadata. What metadata would be useful to collect about a cell phone? How does that overlap or differ from a laptop?

Taxonomy

A taxonomy is a specific instance of a classification method that is used for organizing information, including types of metadata and their values. For example, if you're organizing shoes, you could choose to use US sizes (such as 11½) or international sizes (such as 44) or both. These choices dictate other parts of your product and user experience. If you only store US sizes of shoes and want to sell shoes in Europe, you’ll have to do some work to add or adapt those existing sizes for your new market.

Taxonomies come in two styles: fixed and open. A fixed taxonomy is like the shoe sizes above—set once and applied to all items that you're categorizing. This is helpful when your content isn't changing much, like if you run a shoe store or a news website. It's easier to add, search, and filter items when there's a standard set of categories and metadata. For example, if you want to let users search by color, you could use red, brown, green, and black—and only those colors—as search options. It doesn't make as much sense to have options like sea green or taupe in your taxonomy because most people don't look for shoes at that level of specificity, and you could explode the number of color options in your taxonomy.

An open taxonomy is one where users can add whatever values they want at any time. This is mostly used in hashtags. You can create a new hashtag whenever you want, and they're largely self-descriptive, like #UX for user experience-related issues. They come with incredible flexibility, and you can add new ones with ease. You give up control over their organization and use, however, which can impact searching and discovery.

Card sorting

Card sorting is an excellent tool that can help you organize information quickly. In short, you put all the things you want organized on cards, have people organize them into groups, then find a middle ground between all the groups that people have created. It's a fun method because it challenges people to think creatively while doing a tactile activity.

You can view an example of this here. (Note that this video depicts an open card sort. Continue reading to learn how this differs from a closed card sort.)

To run a card-sorting session, you need to take care of a few tasks. First, decide what needs to be organized. If you're trying to figure out the categories of products for your e-commerce stores, you should create a list of items that you want categorized. You can either create the list yourself (a closed card sort), or you could give participants a prompt and have them come up with the lists themselves (an open card sort). An open card sort is usually a better choice if you're dealing with user-generated content or sites that use tagging over fixed taxonomies.

Next, you'll need to recruit people for your tests. You can often use people in your office for this kind of exercise. Many other kinds of UX research exercises require actual users of your product. But when it comes to categorizing things, you'll get enough variety from anyone—unless there's specific domain knowledge required to complete the task. Card sorting doesn't take much time, so you don't have to worry about wasting others' time to do this.

When you're ready to run the test with someone, introduce them to the task. Assume that this is a closed card sort. Let them know their goal is to take the cards you've provided and organize them into groups, using whatever criteria they want. Ask participants to make sure every group has at least two cards in them—there should be no lone cards. When they're done, ask them to give each pile a name based on the category the cards represent.

While the groups are sorting cards, pay close attention to what they're doing and how they're doing it. Often, they'll stumble on a few items, or maybe they'll reorganize many cards after they've started. These are good starting points for a discussion after they're done.

When they're done, ask them about their choices, especially if you notice any cards they had trouble organizing. If there's an "other" pile (and there often is a set of cards they couldn't figure out), try to find out what would make those easier to sort.

Finally, record all the responses—which cards are in which groups and what those groups are named. You can then take all the responses and sort them together into the final groups. If you want, there are many online tools for card sorting that can even suggest potential groupings based on the average response.

Other information architecture approaches

Information architectures feed other aspects of product development and design, so you should think about these issues when you're working on your IA.

Search

A search feature is the most common way of finding most things in modern products. In a way, searching is the anti-IA. Most people would rather type a few terms to find what they're looking for than sift through categories and menus. But a search engine is only as good as the data inside of it. Information architecture techniques are often used to create the search database. This process ensures that searchable content will match users' search queries.

You can combine your taxonomy with technology, like natural language processing (NLP) and stemming, to take search terms and match them with your metadata. NLP tries to take natural language and translate it into a form that computers can understand. Stemming helps translate verb tenses and singular and plural words into canonical terms so they fit the terms in your search taxonomy.

Customization and personalization

Another anti-IA pattern is to personalize your users' experiences so that you always show them the most appropriate content at any time. For example, if you run Amazon's product search, and you know a particular shopper always buys Dove soap, you should show Dove as the first product in their results whenever that shopper searches for soap.

Technologies, like machine learning and data modeling, help create these kinds of personalized experiences. They're especially successful in e-commerce settings where you can increase the likelihood of users purchasing items by showing them exactly the right product. You can even personalize experiences for first-time visitors. You can make some intelligent guesses about who they are and what content is most appropriate for them, based on their location, the site that referred them to you, what ad they clicked on, and more.

Using Optimal Sort

Image source: Optimal Workshop

Image source: Optimal Workshop

It is recommended that you use Optimal Sort as your software for this activity. Optimal Sort is a popular card-sorting tool that lets you conduct a card sort with a limited number of participants for free.

Getting ready to facilitate a card sort

So far, you've had a chance to refresh your understanding of card sorts, try one out as a participant, and create a set of cards that will generate meaningful insights. You've also recruited a dozen people to participate: two in live interviews and ten more in survey-style sorts.

In this checkpoint, you'll go through the live process of facilitating a sort, including learning about your role as a facilitator and listener. You'll be guided through the steps involved in moderating a sort, and—most importantly—you'll practice facilitating with participants.

Using card-sorting software (Optimal Sort)

There are a few similar industry-standard tools for conducting card sorts. In this checkpoint, you'll go through the process of using Optimal Sort from the company Optimal Workshop. It's perhaps the best known tool for this purpose and will allow you to run a small study with a free account.

Image source: Optimal Workshop: Card Sorting

Image source: Optimal Workshop: Card Sorting

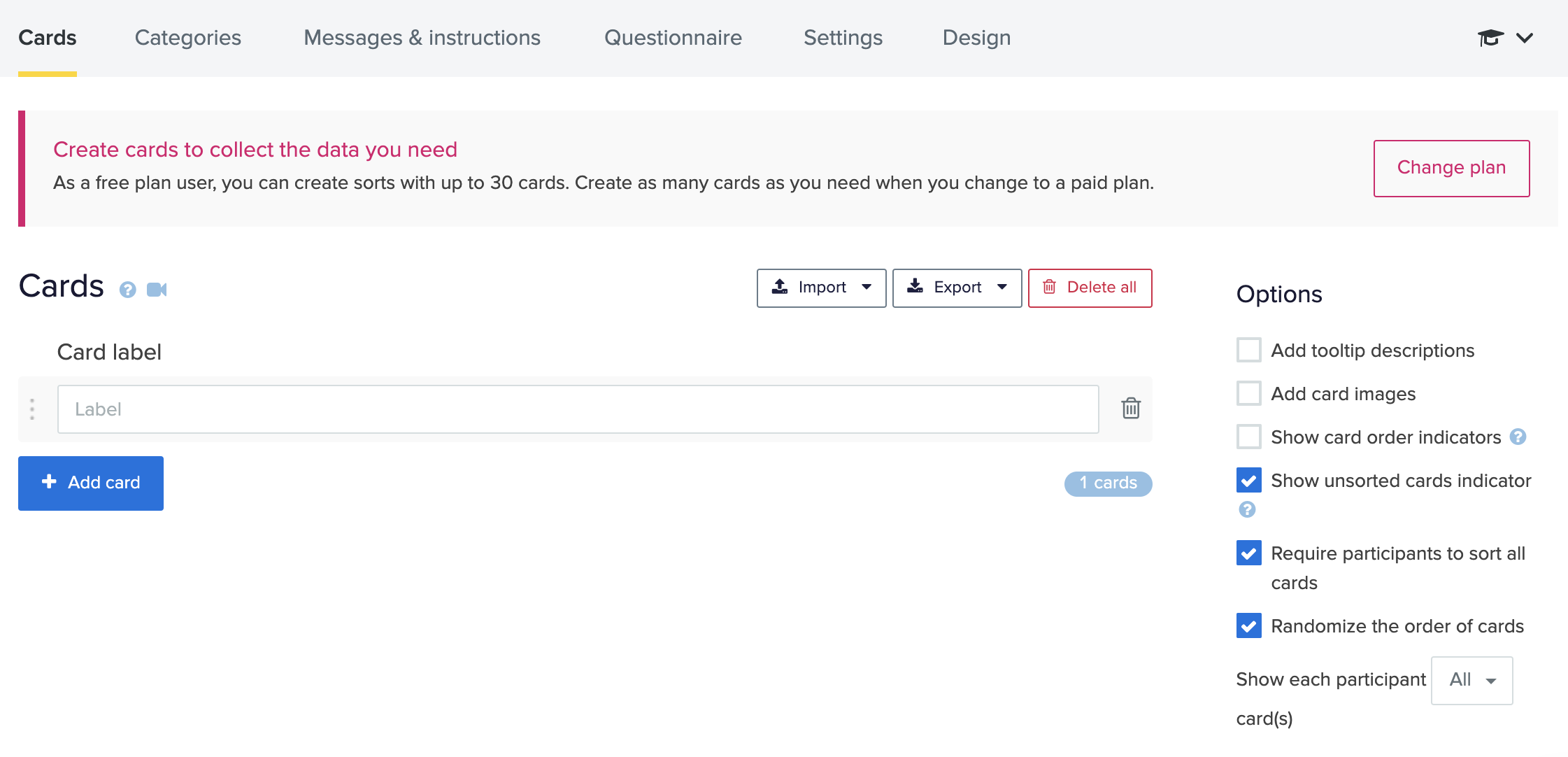

First, if you haven't already, visit Optimal Workshop to set up a free account. Then, make your way to Optimal Sort by selecting Start card sorting. From there, you can walk step by step through the process of creating a study.

Here are a few tips to help you.

Creating cards

In Optimal Sort, the first screen you'll see when you create a new card-sorting study is the Cards tab. You should select Import and then Bulk import cards. You can then copy and paste the cards you've already written and tested out for clarity.

Selecting categories

From the Categories tab, you'll choose the type of sort you'd like to conduct. For your project in this module, you should facilitate an open card sort.

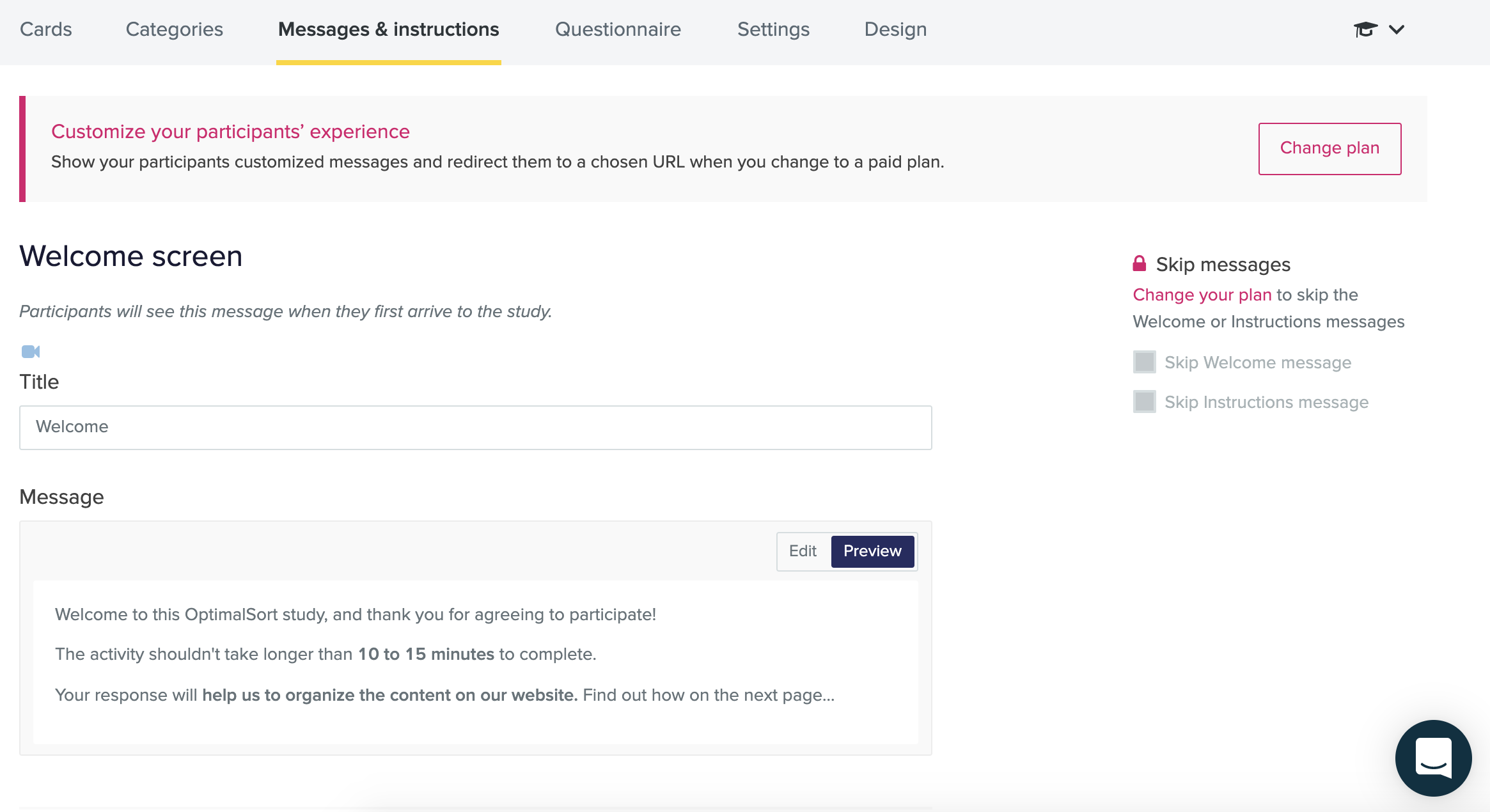

Writing messages and instructions

Optimal sort lets you modify the introductory messages and instructions that a participant will see before they start a sort. Whether you modify these introductory messages depends on your audience and needs. For this project, it is recommended that you leave the instructions as they are currently written. But if you'd like to personalize the Thank You message, go for it.

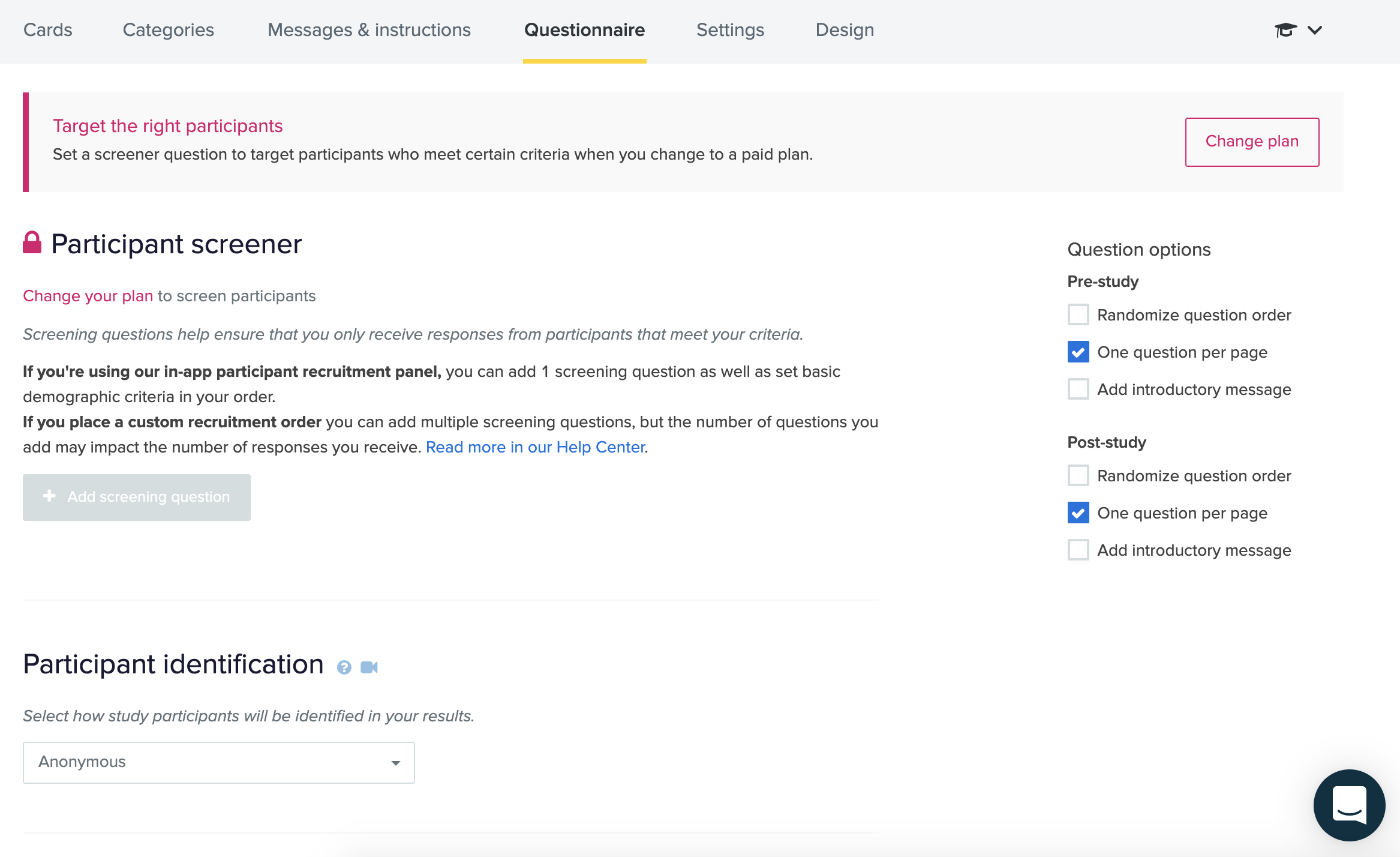

Adding a questionnaire

With a paid plan, you have the option of adding a screener to the card sort. In a real-world client or company setting, you could use this option as part of an unmoderated sort. For your project in this module, however, you won't need to use an integrated screener because you have prescreened as part of your planning and recruitment process.

You also have the option to add pre-study and post-study questions that are written in survey format. In a real-world setting, you might add a few questions to help contextualize the results. For example, you might ask questions to learn how often the participants shop at the site you're testing or whether they use competing products. (Recall the questions that you saw when you tried the Bananacom demo: "What services do you currently subscribe to?" and "How many times per month do you use the website?")

For this project, you can ask any survey-style questions that will support your research goals. As a best practice, limit the number of questions you ask. Two to three questions is typical; more than six would likely feel burdensome to your participants and could cause them to drop off before submitting results.

Recruiting through the tool

Optimal Sort and similar industry-standard tools allow you to recruit participants directly from these companies' participant pools. Be aware that these are paid services. You will not be using this recruiting option for your work in this course, but it is helpful to be aware that these services exist. In your future work, you might choose to use in-tool recruiting if your project budget allows for it.

Previewing and launching your study

Before sending the link out to participants, it is recommended that you preview your cards and settings. Make sure that the questions are clear and that the cards appear as you've intended.

When you're satisfied with the appearance of the study, launch it. From this point forward, the study link (available from the Recruit tab) will be live, and data that you collect from participants will appear in the Results section of the study.

Unmoderated card sorting

As you've already learned, an unmoderated sort is like a survey: the researcher sends a study link to participants, and they respond and submit results on their own time.

In unmoderated studies, the researcher is responsible for planning the research, preparing the study in the software (using the steps you just learned about), sending out the link, and then analyzing results after a period of time. For your unmoderated sort in this module, you will be asked to gather data from at least 10 participants.

The benefits of an unmoderated sort, as you've learned, are similar to the benefits of surveys: you can gather information from a large number of people to determine trends. But the downsides are also similar: you can see trends in the data but won't necessarily understand why the trends exist. For this reason, it's helpful to also conduct a moderated sort.

Moderated card sorting

So, how do you conduct a moderated sort using a software tool? You can use the study you've already created in Optimal Sort. But instead of sending out the link and asking participants to complete the sort on their own time, you'll join the participant and observe them sorting in real time over web conferencing software (like Google Hangouts or Zoom). Here are a few tips.

Building a session guide

Before conducting a moderated sort, take time to create a session guide, just as you would for a usability test. Remember that the session guide is intended to support you as the moderator. You can write out a script for yourself (or a list of the major beats of a script) so that you remember what to say and how to say it when you're in conversation with a participant.

Here's the recommended section structure:

- Welcome. Log into a web conferencing session with the participant. Welcome them, and give them a high-level overview of what the session will entail.

- Warm up. Start with a very short warm-up interview. Ask your participants a few simple questions in relation to the topic of the card sort. For example, if your study relates to a streaming TV service, ask them about their TV-watching preferences and habits.

- Introduce the card sort and think-aloud protocol. Next, let them know that you're going to transition to the card sort. Ask them to think aloud—just as you would for a usability study. Remember to stress that there are no wrong answers. You're there to learn from them, not test them.

- Send them the card sort link, and ask them to share their screen. You can typically send them the card sort link through the chat function on the web conferencing software.

- Observe the sort. Let the participant work their way through the card sort and related questionnaire. Use best practices for think-aloud protocol: Ask participants to vocalize their thoughts while they're completing the sort, and remind them that there are no specific right or wrong answers.

- Wrap up. When they're finished, thank the participant, and offer them the opportunity to ask questions or share their final thoughts.

Listening as a researcher and probing for details

So what should you listen for when you conduct a moderated card sort? As in a usability test, your job as a researcher is to listen for nuance and reasons for the participants' choices.

Aim to discover the "why" behind the categories they create: Are they making assumptions about the content? Are they suggesting categories that might be even more helpful or important? Are they grouping several unknowns together simply because these topics are not something they'd use? If a participant is quiet or just reading the cards as they go, you can probe them gently to share more thoughts. Starting with saying, "Tell me more about…" can help.

A great way to engage a participant in thinking aloud during a card sort is to ask them to explain their overall system when they've finished. You can encourage them to share their thoughts with a prompt that encourages reflection. Here are some example prompts:

- "Thanks for sorting the cards. Tell me more about the system you've created here."

- "Tell me a bit more about why these categories work for you."

- "Are there any other ways that you might want to categorize the cards?"

If they've created categories that aren't clear to you, ask them for clarification. Remember to place them in the role of teacher so that they don't feel like they've done something wrong. Here are some example questions to ask:

- "Tell me more about the category called ___. As the designer of this system, what else would you put in that bucket? What else might you expect to find there?"

- "I see that you've created a category called __. In your system, what are the main differences between that category and the one called __?"

Overall, be curious and enjoy your time with participants. For your work in this course, practice, listen, learn, and be flexible with yourself as a beginner in this process. If you'd like to take it further and interview more people, then go for it!

Activity 🎯

You run e-commerce for Kickstarter and are working on adding new categories of products to your site. Find a list of potential product types here. Run a card sorting exercise with yourself and at least two other people to group these product types into categories. Use Optimal Sort to do this activity.

Create a final report and add it to your notebook/notion page. It should include all of the following items:

- A list of categories, including the name of the category and the items that belong in it

- A link to the videos of the card-sorting sessions you ran and photos of the final sorts

- A short paragraph summarizing your key learnings from the experience