8.7 Prototypes

When designing interfaces and forms, it helps if you can test out how they'll work before they're totally complete. A prototype is a simplified version of the final product you're creating. It may not have all the bells and whistles of the real version, but it's enough for testing and validation. It should demonstrate the core functionalities the product should have without developers spending the time to create those features.

You can create prototypes for physical or digital products. In this checkpoint, you will learn how you can use tools to create those prototypes, even turning your wireframes and sketches into functioning, clickable experiences.

By the end of this checkpoint, you should be able to do the following:

- Explain the value of creating and testing prototypes

- Use prototyping tools to turn sketches or wireframes into interactive prototypes

What is a prototype?

A prototype is a version of a feature or product that's a portion of the whole. They're used for testing and validation, especially if the final version will be difficult or expensive to build, or if you have key questions you still need to answer about the final version. Prototypes are used in all kinds of industries—automotive design, software creation, hardware devices, and others.

Prototypes can range from just-for-show to somewhat functional. You don't need the whole, final product to demonstrate how it will work to a potential customer, and you don't need to sort out all the details for people to give you feedback about it. Similarly, prototypes can cover some to all of the features you intend to build.

It's often easier to create a prototype than the real version of a product. How far you go depends on the time you have and what you want to learn from the prototype.

How we use prototypes

The most important use of prototypes is to communicate your design ideas. A prototype reduces ambiguity about how something will work. By showing an almost-real version of a product, your users don't have to imagine how it will work; they can actually experience how the product will work for them.

You can learn almost as much with a prototype as you can with the real thing, and you'll save yourself considerable time and effort by doing your testing before investing in the real version.

A prototype is also a good tool for when there are specific details that can only be demonstrated. Interface flourishes, like animations or transitions, can't be produced in wireframes; they have to be experienced. Similarly, if you're building hardware products, having a prototype gives literal weight to your idea. Seeing your hardware product on a screen is not an acceptable substitute for a physical prototype.

Prototypes are also great for getting feedback and collaborating on designs. When someone has the actual product to test with, they'll be able to give you much more concrete feedback than will those who have heard a description or seen a wireframe.

Types of prototypes

Prototypes can come in all shapes, sizes, and form factors. You should be familiar with the most common ones, and choose the form to fit each specific situation.

Paper prototypes

A paper prototype turns sketches or wireframes into a "usable" version of a product simply by printing it out on paper. Imagine you have a home page and login page that you want to test. You could print both out on paper, show someone the home page, and ask them to log in as if the paper was the application. When they "click" the login link, you can act as the application logic—swapping out the home page on paper for the login form.

This kind of prototype can expand to any number of interactions. Just keep in mind that you'll need a sheet of paper for each state of each page you want to test. Continuing from above, maybe there's a difference between the logged-out and logged-in home pages. If so, you'll need two versions of the home page for your paper prototype. You can show someone the logged-out home page, have them "log in" on the login form, then return to the logged-in home page. You'll need as many varieties of pages as paths you want to demonstrate.

Paper prototypes are low effort and cost, but when you use them for demos, you could miss feedback that you might have gotten with a higher-fidelity design. Similarly, people may be more comfortable seeing the prototype as a clickable version on their desktop than they would on paper; there will be less of an imaginative leap required.

Clickable prototypes

With today's design tools, you can easily create clickable prototypes out of your sketches and wireframes. If your designs are hi-fi enough, your users will have an almost seamless experience trying out your product and features.

When using apps like Figma, InVision, and proto.io, you can even push your design to a desktop or mobile device so you can preview it as it might appear on that device.

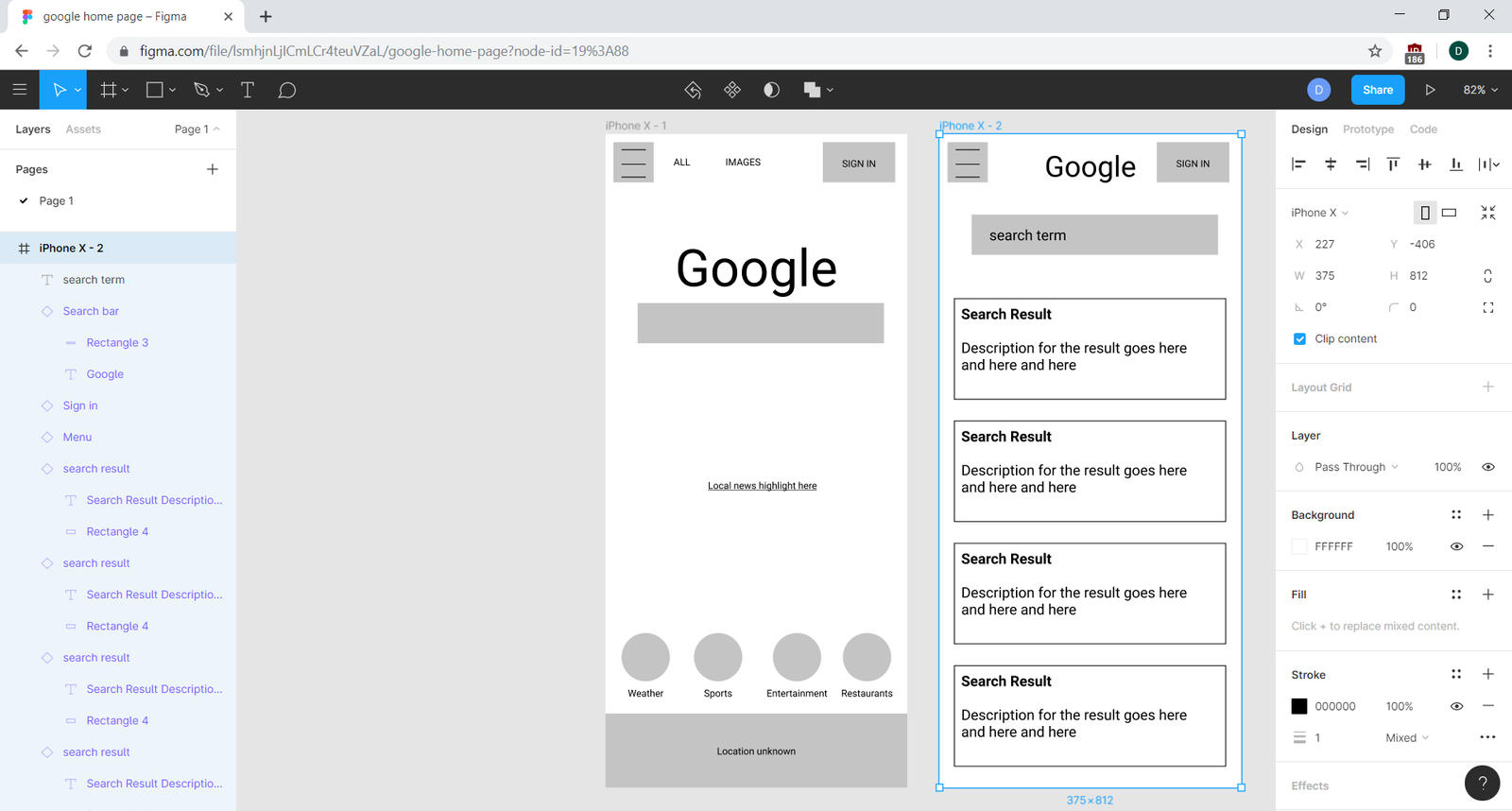

Follow along with Figma on another window or using the video below to create your first prototype. First, you'll need a couple of wireframes on the same page. Below is an image of the Google home page wireframe you created in an earlier checkpoint. How might you prototype the search experience? What other pages will you wireframe, and how will a user interact with them?

First, add a new frame—hit F and choose the iPhone X design on the right panel. Fill in that frame with a second page—in this case, the search results page.

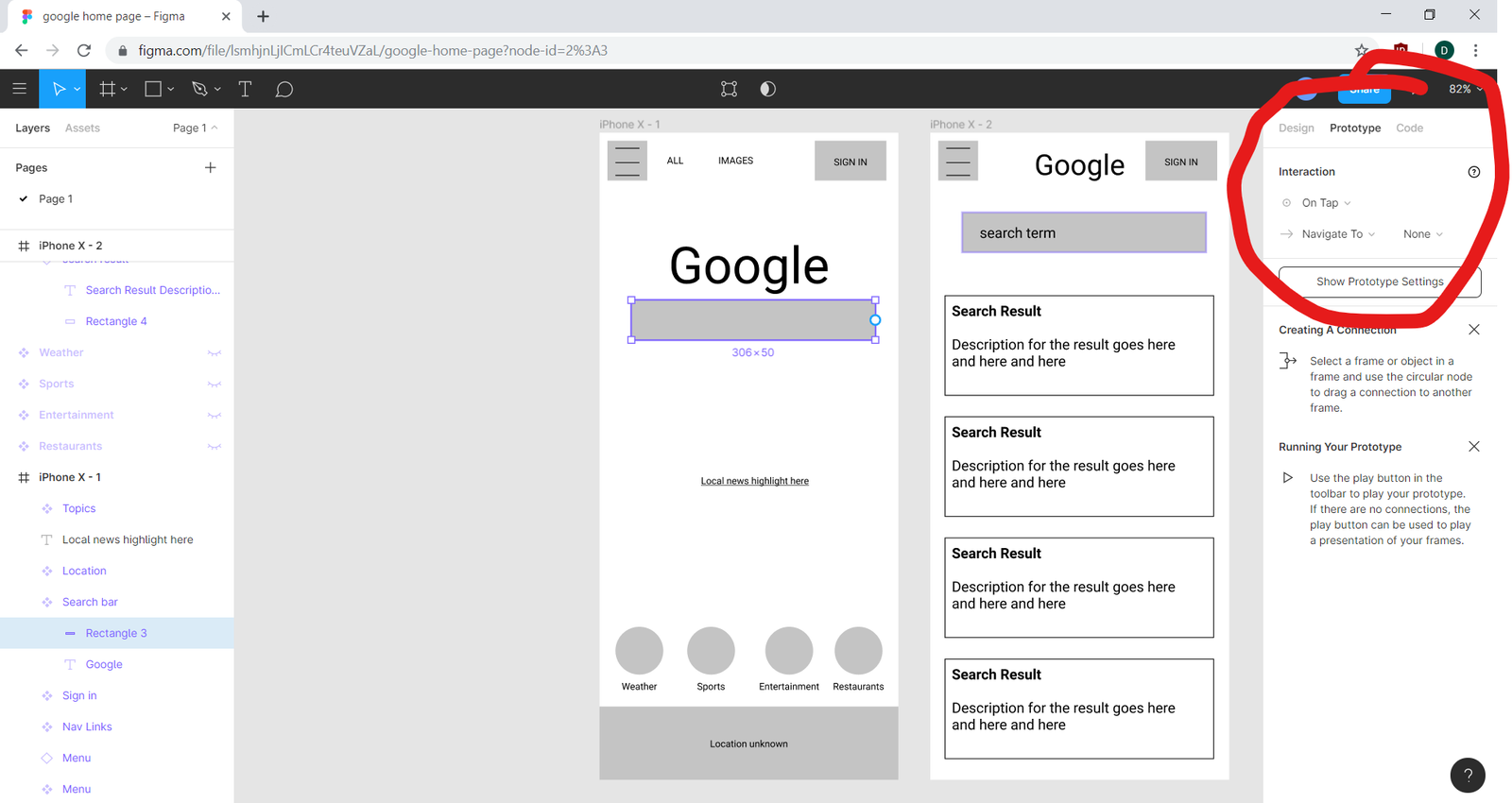

For your prototype, the goal is to simulate a search—if you know what you want to search for, you imagine typing it in, then you touch the search bar to submit it. So select the search bar in your mockup and click the Prototype tab in the right panel. You'll see a new menu with options for creating a prototype.

For this one, make it go to page two when tapped. Use the Interaction options to set it to "navigate to" your second page on a tap. It should look like the image below when done. Note the arrow between the search bar and the second page, indicating the interaction set up.

Finally, hit the play button in the upper right corner. This will start up a prototype using your settings. If you click anywhere in the background, you'll see the search bar highlight briefly. That's your indication that it's a clickable element. Click it and it will take you to page two.

You can also use the video below to help you create your first interactive prototype.

And just like that, your wireframe now works like a clickable prototype. Many other popular wireframing and prototyping applications have similar functionality. You should try a few of these tools to see which you like best—InVision and proto.io are a few popular options.

You can also use Figma's mobile app for showing wireframes. Download it off the Google Play or Apple App store, log in, and then choose any of your designs to show on your mobile device. It's best to use the web or desktop prototypes when presenting your design and the mobile app when testing designs for mobile with users.

If you have sketches but not wireframes and want to use them in a prototype like this, you can take digital photos of your sketches, then import the images into Figma (or your tool of choice). To create interactive controls on sketches, add a transparent box over your image in the places that should have interaction, and follow the steps detailed above.

Other prototype examples

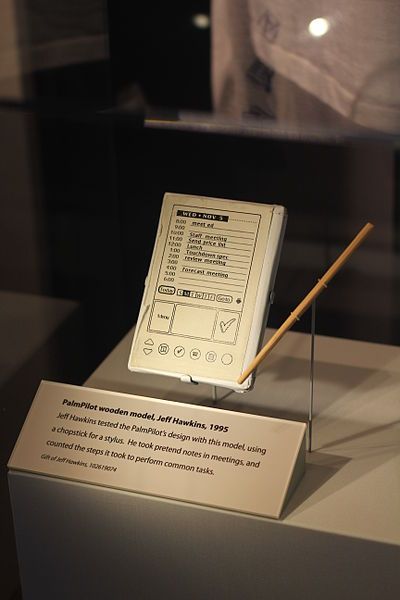

When making physical products, your prototype could be anything from very low-fi to almost complete. The prototype for the PalmPilot, an early mobile device, was a piece of wood with a piece of paper taped to it. The designer would pretend that he was taking notes or scheduling meetings.

PalmPilot wooden model (1995), Computer History Museum. Source: Wikimedia

With 3D printing and electronics fabrication now more accessible than ever, you can create high-quality physical, functioning prototypes with ease and speed.

Testing your prototypes

Prototypes make testing and validating your designs fun and easy. If you have sketches or a paper prototype, you can give someone a task to complete, have them explain what they'd do on a given page, and act as the program to flip to the next page that they should see.

If you have a functional or interactive prototype, you can grab people in the hall or at their desks to walk through the prototype with you. You'll still need to pay close attention to how testers navigate your prototype. For example, it may not be obvious to them which elements are interactive and which aren't. Still, you'll get good feedback, and the person using it won't have to think or use their imagination as much as they would with a paper prototype or wireframe.

Practice ✍️

Create a three-page interactive prototype for a fictional app of your own creation. You can have any three pages, for instance: a home page, a registration page, and a search page. You'll be using this prototype for the next checkpoint, too, so think carefully about what you create.

Create the wireframes using a tool of your choice. Make sure all the appropriate buttons or links work correctly and trigger the expected interactivity. For instance, if there are links between the three pages, the "home" link should always take you to the home page.

If you want to go the extra mile, you can also do the following:

- Add filled-in states in your prototype. For example, start with a blank registration form, then set it up so a tap on any field goes to a mockup of a page with all the fields filled in.

- Show logged-out and logged-in states for each page. If a user starts logged out on the home page and then goes to the registration page, have them tap a field on the registration form to "fill it out," then a final tap on the registration button lets them "sign in" and revisit the home page as a logged-in user.